<– Batteries

To Chapter 6- Climate Solutions (part 2) for 2050 –>

Heating

To achieve the global emission targets for 2030, a further 3.3 GtCO2-eq needs to come out of the fossil fuel heating of buildings. Needed first: new building codes that require the incorporation of electric (including heat pumps) rather than fossil fuel heating and cooking systems for all new buildings. In 2022, U.S. sales of heat pumps surpassed those of gas furnaces for the first time.[1]

There were approximately 85 million single-family houses, 32 million apartments and 5.9 million commercial buildings in the US in 2020.[2] These are being added to or replaced by construction of approximately 373,000 apartments, 614,000 single-family houses and 407,000 commercial buildings each year. That’s roughly 1.3 million new buildings/units per year, or a bit more than 1% of the total building stock of the country.

If all new buildings met the highest fossil-free standards, it would reduce CO2-eq emissions by approximately 5 MMT per year, or 50 MMT in the US by 2030. This is clearly not enough to meet the targets, so a major goal must be the retrofitting of buildings to replace all fossil fuel-based heating (and cooking) systems with electric ones by 2050—a further reduction of 630 MMT.

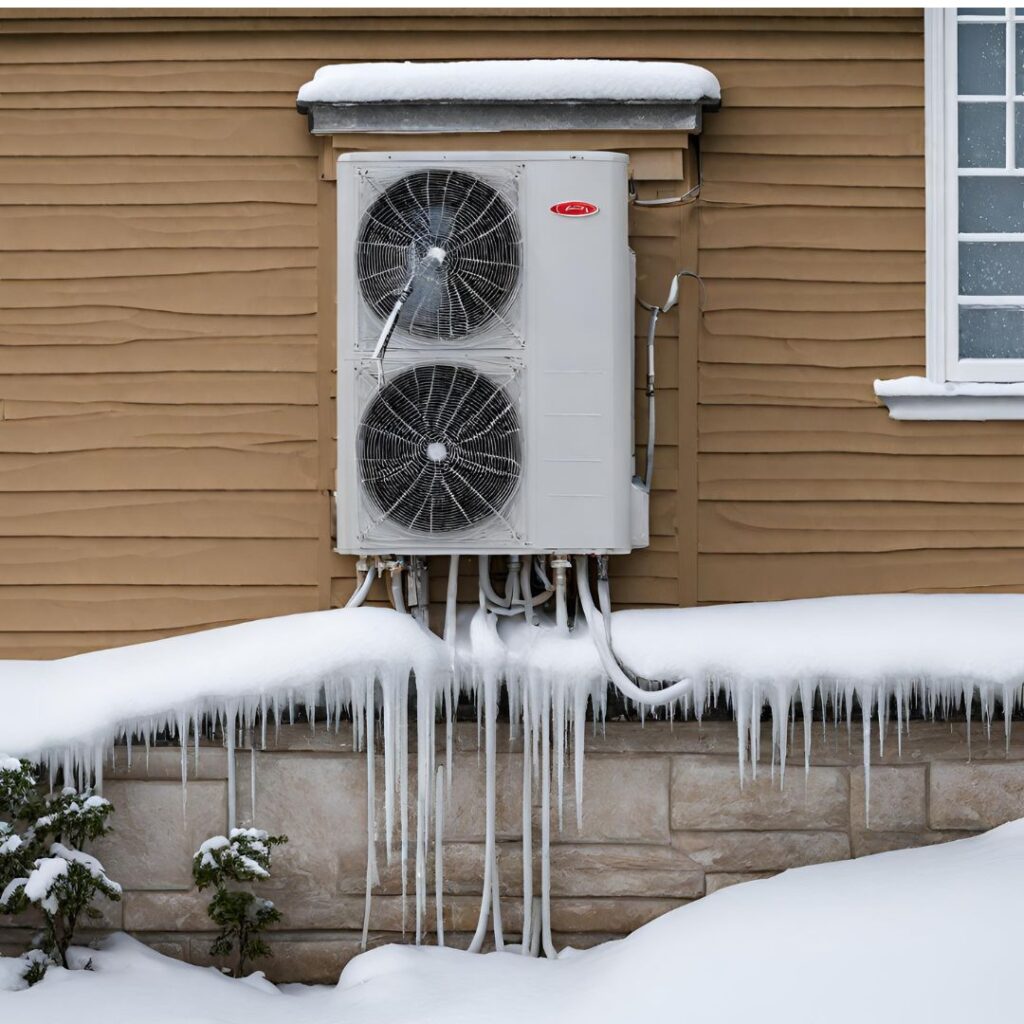

Heat pumps and refrigerants

Air-sourced heat pumps are the most efficient form of heating for most of the earth’s climate zones. These can now heat homes in temperatures as cold as -17°F. Below that, air-sourced heat pumps are so far insufficient, and ground-sourced “geothermal” heat pumps are needed. Electric resistance heaters are effective in all temperatures, but are very energy-intensive and therefore expensive to run.

The irony of modern-day heat pumps is that they almost universally rely on the refrigerant R-134a, a greenhouse gas with GWP of 1,240, meaning that it is over 1,000 times as potent as carbon dioxide (see below and chapter 3). This refrigerant is to be phased out under the Montreal Protocol, but currently the US Environmental Protection Agency is allowing its continued use until January 2025.[3]

Heat pump manufacturers and installers in the US want to use up their existing stockpiles of R-134a heat pumps, and have made it virtually impossible to install any other type at the present time.

Industrial emissions

Industry overall accounts for 24% of global emissions, or about 14 GtCO2-eq in 2019. This is the second biggest source of emissions after the energy sector. About 65% of those emissions (nearly 10 GtCO2-eq) comes from the production of cement, steel and certain chemicals that require heating to very high temperatures (above 500°C).[5] Those industrial processes will have to transition to fossil-free sources of energy in the long run, but they are not going to be easy to decarbonize in the short term.

The remaining 35% of industrial carbon emissions, however, come from other activities that are more amenable to immediate decarbonization. About 19% of the fossil fuel used in industry is for processes requiring only low-temperature heat (up to 100°C). Another 16% is for running industrial machinery, heating factory floors, etc.[6]

If these low temperature requirements were met with industrial heat pumps similar to those used to heat residential and commercial buildings, and industrial machinery currently running on fossil fuels were instead electrified like cars and trucks, that would be another 4 GtCO2-eq that could be cut from global emissions, bringing us down to 25.8 GtCO2-eq.

Banning HFCs

In the 1980s, it was discovered that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), used mainly for refrigeration, air conditioning and aerosols, were destroying the ozone layer that protects the earth from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. CFCs were banned by the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement that went into effect in 1989.

CFCs were largely replaced by hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), another type of chemical that served the same purposes as CFCs but without affecting the ozone layer.

Unfortunately, HFCs do contribute to climate change. In fact the most common HFC in use, R134a (see above), has global warming potential (GWP100)[7] over 1,000 times that of carbon dioxide. Other HFCs have a GWP as high as 14,800.[8] In 2016, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol was agreed, phasing out the use of most HFCs worldwide by 2050. It entered into force in 2019 after 65 countries had ratified the amendment. But the US was not among them.

The US Senate finally ratified the Kigali Amendment in September 2022. This will require US companies to phase out 85% of HFCs in use by 2036. If this process were to be sped up to achieve an HFC-free world by 2030, that would reduce global emissions by another 1.4 GtCO2-eq.

[1] Olano, M. V. (2023, February 10). Chart: Americans bought more heat pumps than gas furnaces last year. Canary Media. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/heat-pumps/chart-americans-bought-more-heat-pumps-than-gas-furnaces-last-year

[2] U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2023, March). Consumption & Efficiency. EIA. https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2020/hc/pdf/HC%201.1.pdf,

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2012). CBECS 2012: Building Stock Results. EIA. https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/reports/2012/buildstock/,

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2022, December 21). 2018 CBECS Survey Data: Table B1. EIA. https://www.eia.gov/consumption/commercial/data/2018/index.php?view=characteristics#b1-b2

[3] See International Institute of Refrigeration. (2023, January 26). US to ban high-GWP refrigerants. IIR. https://iifiir.org/en/news/us-to-ban-high-gwp-refrigerants

[4] Photo: V. Elson

[5] Rissman, J. (2022). Decarbonizing Low-Temperature Industrial Heat in the U.S. In Energy Innovation. (p. 5). https://energyinnovation.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Decarbonizing-Low-Temperature-Industrial-Heat-In-The-U.S.-Report-1.pdf

[6] Ibid, p.7.

[7] See Chapter 4.

[8] Environmental Investigation Agency. (n.d.). What Are Hydrofluorocarbons?. Retrieved September 18, 2023, from https://us.eia.org/campaigns/climate/what-are-hydrofluorocarbons/