From Chapter 17 of Warheads to Windmills

Jump to: Divestment ~ Boycotting ~ Stigmatizing

With a political system in the United States that is so heavily dominated by large corporations and their vested interests, one possible avenue for change is through the corporations themselves. Corporate directors and major shareholders are ultimately driven by one thing: profit. They don’t care if they make nuclear warheads or wind turbines, as long as there is money to be made. That means they are susceptible to being influenced through their profit-loss statements, their balance sheets, and their reputations.

These corporations operate in numerous countries. They have factories, offices, suppliers, customers and investors all over the world. That’s why the Nuclear Ban Treaty and a potential Fossil Fuel Treaty are so important. Countries that are party to these treaties can subject the companies to vastly more powerful pressures than anything an individual US consumer or investor can apply.

But individual consumers and investors are powerful in numbers: banks, financial institutions, faith communities, colleges, businesses, hospitals and especially cities and states can pressure the corporations from within the US while other countries exert pressure from outside. That’s a combination that can ultimately move the complicit corporations from warheads to windmills.

Many people believe that divestment, boycotts and other attempts to put pressure on large corporations are futile, and they point to various academic studies to back up that belief.[1] For example, if for moral reasons one person sells their stock in a given company, someone else with fewer moral scruples can simply buy it, cancelling out any possible effect the first person might have. Similarly, boycotting goods or services matters little to a company if others are willing to continue buying from them.

But corporate profit does not come solely through the selling of goods and services. Corporations have to care about their public image, because that affects their corporate reputation (“reputational risk”) and the bottom line value of their brand (“brand equity”).[2] They also have to care about who is buying and selling their stock, because if even a small number of investors lose confidence in the corporation (“investor anxiety”), it can cause a sudden drop in its overall value (“market capitalization”).[3] And they have to care about intangibles, like whether their activities carry any risk of being considered illegal or unacceptable at some point in the future (“legislative risk”), or whether they may be forced to abandon resources they are currently including on their balance sheet as valuable assets (“stranded assets”).[4]

The people who run and invest in these companies are also human beings. They all have families, friends and colleagues, people they listen to and care about. They may be influenced by religious figures, academics, or philosophers.

So while they may seem all-powerful in terms of their impact on public policy and the media, they are also susceptible to being influenced through all kinds of other channels, whether social or economic. Today these corporations almost universally maintain a presence on social media, where they are especially vulnerable to public attitudes towards them, even when these do not directly translate into customers or sales.[5]

Divestment

Perhaps the best-known example of a divestment campaign is the one that sought to end apartheid in South Africa.[1] Divestment was only one of the many tactics that successfully brought apartheid to an end, but its significance shouldn’t be underestimated. International banks were increasingly unwilling to loan money to companies in South Africa, international companies were letting go of their South African subsidiaries, and international investors were selling off their South African stocks. These factors impacted the South African economy, causing a flight of capital out of the country, rising inflation, and a shortage of loans with which to invest in new equipment and infrastructure, resulting in a declining industrial base. The South African government was presented with an increasing shortfall of the capital it needed to rebuild the economy.[2]

Other divestment campaigns have taken on tobacco companies,[3] gambling, private prisons, farm workers, handguns and many other issues, all with mixed results to date. Divestment was a tool used in the 1980s against nuclear weapons, but it played a relatively small role compared with other profiteer-pressuring tools (see below).

Fossil fuel divestment

According to the Global Fossil Fuel Divestment Database,[1] roughly 1,600 institutions with responsibility for more than $40.5 trillion in total assets have so far committed to divesting from fossil fuels worldwide. These include roughly 570 faith-based organizations, 250 educational institutions, 185 pension funds, 190 philanthropic institutions, and 175 municipal, state, provincial and national governments.[2]

Most institutions divesting from fossil fuels use the Carbon Underground list of the 200 publicly traded companies that hold the largest coal, oil and gas global reserves.[3] Koch Industries does not trade on the stock market, so although they are the company spending the most on lobbying Members of Congress, they are not on the list for divestment.

Faith communities

Faith-based organizations have led the way globally in divesting from fossil fuels and other products over many decades.[4] These include the Vatican, with all the weight that that carries among over a billion Roman Catholics around the world.[5] Other national or international faith-based organizations divesting from fossil fuels include the Church of England (Episcopalian), the Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), the Church of Sweden (Lutheran), Episcopal Church USA, Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, Islamic Society of North America, Lutheran World Federation, Quakers in Britain, Presbyterian Church USA, United Church of Christ (US), Unitarian Universalist Association, and the World Council of Churches.[6]

These organizations carry a certain moral authority in most countries, and they often have responsibility for considerable financial assets. When faith communities stand up for certain moral principles and put their money where their mouth is, they can make a significant impact.

Higher education

Colleges and universities also have a special role in representing science-based knowledge and the collective wisdom of the ages to the rest of society. They may also have large endowment funds currently invested in fossil fuels and nuclear weapons companies. Fossil fuel divestment campaigns at some of the most well-known and prestigious educational institutions have had some successes, and others are still ongoing.

In 2014, the University of Glasgow in Scotland was one of the first universities to commit to divesting from fossil fuels.[7] Since then, universities and colleges across the US and Europe have taken similar steps, including both Oxford and Cambridge Universities in England, who between them have assets of almost £21 billion ($25.5 billion).[8]

Among US colleges with the largest endowments, Harvard, Princeton, Cornell, and the Universities of Michigan and Washington have committed to divesting from fossil fuels. Stanford University has so far divested only from coal and not from other fossil fuels,[9] while Yale, Emory, and some others are still only partially divested.[10] Nevertheless, the trend lines are clear. Students are demanding that their colleges and universities divest from fossil fuels.

Governments

So far, Ireland is the only country to have committed to fully divesting from fossil fuels.[11] In the US, Maine passed legislation in 2021 committing its state pension fund to divest from fossil fuels, and the state of New York announced plans to divest its $225 billion Common Retirement Fund from fossil fuels, without any legislation involved.

Cities and towns are the biggest stars of government-led divestment. At least 50 towns and cities in the US have so far committed themselves to divesting from fossil fuels, including some very large ones like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Denver, Boston, Seattle, and Pittsburgh.

While it’s impossible to prove cause and effect, the fact is that this level of divestment parallels the growing commitment of US politicians of both parties to take climate more seriously. And at least one report suggests that fossil fuel investments have lost a fifth of their value during the last decade, while investments in renewable energy have increased in value.[12]

Potential legal basis for divesting from fossil fuels

There is not yet a treaty similar to the TPNW to ban the burning of fossil fuels, but a Fossil Fuel Treaty could change that.[13] Until now, climate agreements like the Paris Agreement of 2015 have nothing to say about divestment. Indeed, the Paris Agreement does not even mention fossil fuels.[14] While fossil fuel divestment is gaining ground internationally and already has more than ten times the scale of nuclear weapons divestment, there is still no agreed upon international legal basis on which to justify divestment.

Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria are used by many investors to justify investments in certain companies. These may include climate-related criteria like whether the company is working to reduce its carbon emissions, but there is no basis for excluding investments in a company because it is a major fossil fuel extractor or uses its profit to promote climate misinformation, lobby for fossil fuel subsidies, etc.[15]

A Fossil Fuel Treaty would give investors a firm basis for divesting from fossil fuels, and, if fashioned like the TPNW and other similar treaties, would also make it a requirement that countries party to the treaty refrain from “assisting” with the continued dependence on fossil fuels, including financing of them.

Challenges for divestment from fossil fuels

Large oil and gas companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, BP and Shell, already under pressure from fossil fuel divestment campaigns, are suddenly branching out into solar and wind technologies to “balance” their portfolios.[16] Some of this is classic “greenwashing.” But if they’re genuine investments in green technologies, campaigners might look for ways to encourage that development while continuing to target the company as a whole.

Another challenge for climate activists is that some of the largest oil and gas companies are state-run or private companies in other countries, like Gazprom or Rosneft in Russia, whose oil and gas reserves dwarf those of the more well-known American and European brands. The company currently spending the most on trying to influence Congress, Koch Industries, is US-based, but also privately owned, meaning it does not trade on the stock market and therefore no investment or divestment is possible.[17]

Divestment on its own is also a limited strategy for putting pressure on the companies concerned, as long as those who are divesting continue to buy from, and do business with, those same companies. In the case of South Africa, and especially in the case of nuclear weapons in the 1980s, divestment was carried out in conjunction with boycotts and other measures to pressure the companies. On its own, it is doubtful whether divestment would have been sufficient.[18]

In the battle against climate change, as long as people continue to buy gasoline for their cars, natural gas for their home heating and other petroleum products from the big fossil fuel companies, these companies have less to fear from divestment. It will probably take a serious consumer boycott of oil and gas products to finally turn the fossil fuel industry around.

[1] This is the most comprehensive list of fossil fuel divestment commitments available at present, but even this database cannot keep up with the pace of divestment worldwide, so the totals are likely higher in all categories and continuing to rise: https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[2] Based on percentages at https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[3] https://thecarbonunderground.org/

[4] According to Interfaith Power and Light, faith communities have been divesting for at least a century. See https://interfaithpowerandlight.org/faithclimateactionweek/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/02/2016-Divestment-Notes.pdf

[5] Pullella, P. (2020, June 18). Vatican urges Catholics to drop investments in fossil fuels, arms. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vatican-environment-idUSKBN23P1HI

[6] See listing of faith-based organizations at https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[7] Brooks, L. (2014, October 8). Glasgow becomes first university in Europe to divest from fossil fuels. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/oct/08/glasgow-becomes-first-university-in-europe-to-divest-from-fossil-fuels

[8] Adams, R., & Greenwood, X. (2018, May 28). Oxford and Cambridge university colleges hold £21bn in riches. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/may/28/oxford-and-cambridge-university-colleges-hold-21bn-in-riches

[9] Nori, Sathvik (2021). “As Peer Institutions Divest from Fossil Fuels, Stanford Still Wavers,” in the Stanford Daily, Oct 14, 2021. http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2014/ph240/lebovitz2/

[10] See Schick, F. (2016, April 12). Yale to partially divest from fossil fuels—Yale Daily News. https://yaledailynews.com/blog/2016/04/12/yale-begins-divestment-from-fossil-fuels/

[11] See Carrington, Damien (2018), “Ireland Becomes World’s First Country to Divest from Fossil Fuels,” in The Guardian, 12 July, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jul/12/ireland-becomes-worlds-first-country-to-divest-from-fossil-fuels Also complete list of more than 1500 institutions divesting from fossil fuels worldwide at Stand.earth. (2023). Global Fossil Fuel Commitments Database [Dataset]. https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[12] Chestney, N. (2021, March 30). Fossil fuel shares drop in value compared with clean energy, think tank says. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-stocks-energy-idUSKBN2BM3CO

[13] See campaign progress at https://fossilfueltreaty.org/

[14] United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement. In United Nations. https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/convention/application/pdf/english_paris_agreement.pdf

[15] See Anderson, K. (2023, August 2). ESG criteria: what you need to know. greenly.earth. https://greenly.earth/en-us/blog/company-guide/esg-criteria-what-you-need-to-know

[16] Merchant, E. (2018, September 24) For Oil Majors Investigating Clean Energy, It’s About Balancing Risk and Return. Green Tech Media https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/report-for-majors-investigating-clean-energy-its-about-balancing-risk-and-r

[17] See table x.x in previous chapter.

[18] McGreal, C. (2021, May 23). Boycotts and sanctions helped rid South Africa of apartheid – is Israel next in line? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/may/23/israel-apartheid-boycotts-sanctions-south-africa

Nuclear weapons divestment

Nuclear weapons divestment is still comparatively small by comparison to the fossil fuel divestment movement, but it’s significant, and it’s growing.

Banks and financial institutions

More than 50 banks and other financial institutions globally with more than $3.3 trillion in assets under management have so far fulfilled the Don’t Bank on the Bomb criteria for divestment from nuclear weapons companies.[1] DBOTB considers another 50 or so, with more than $22.4 trillion in combined assets under management, to be partially divested from nuclear weapons. [2]

In the US, Amalgamated Bank of New York became the first US bank to fully commit to keeping its portfolio clear of nuclear weapons (as well all other weapons, and military equipment, fossil fuels, and other socially and environmentally unacceptable investments).[3] Faith-based investment companies like Wespath (associated with the United Methodist Church)[4] and Friends Fiduciary (Quaker) are also weapon-free, including nuclear weapons.[5] And a large number of ethical investment funds now offer nuclear weapons-free investment options.[6]

Faith communities

Other faith-based organizations have been slow to divest from nuclear weapons, relative to other divestment movements. The Holy See, which was the first entity to sign and ratify the Nuclear Ban Treaty in September 2017, has only recently established a new investment policy for funds held by the Vatican. This prohibits the use of Vatican funds for weapons and many other things, but some of the guidelines remain unclear.[7] In the Vatican’s more recent investment guidance for Catholic investors, Mensuram Bonam, issued in January 2023, nuclear weapons are clearly among the list of exclusions for investment.[8]

In 2020, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (USA) voted to divest from nuclear weapons.[9] The United Methodist Church has also divested, along with individual churches and Quaker Meetings around the country.[10]

Higher education

Hampshire College in Massachusetts divested from nuclear weapons in 2015.[11] (Hampshire was also the first in the US to divest from South Africa in 1977, and one of the first to divest from fossil fuels in 2011.)

Yale University, which literally wrote the book on ethical investment,[12] has so far only partially divested from fossil fuels and has refused to divest from nuclear weapons.[13] Given the background they have on setting standards for ethical investment, Yale is a prime target for further campaigning on both these fronts. And by combining the case for divestment from fossil fuels with the case for divestment from nuclear weapons, students and faculty at Yale could build a powerful alliance.

Governments

Ireland, the only country so far to have committed to fully divesting from fossil fuels, is also the first State Party to the TPNW to have passed national legislation that prohibits any persons within Ireland to “assist” with the development, manufacture or maintenance of nuclear weapons. It is not yet clear to what extent that will be interpreted in Ireland as including all forms of financial assistance, but already Ireland’s Sovereign Wealth Fund (ISIF) has divested €6 million worth of shares from a (more limited) list of nuclear weapons companies.[14]

Switzerland, which is not yet a party to the TPNW, nevertheless has national legislation that prohibits “the direct granting of credits, loans or endowments or comparable financial advantages, in order to pay or advance costs and expenditures that are associated with the development, manufacture or acquisition of prohibited war materials [including nuclear weapons].”[15]

United States: A number of cities, towns and counties in the US divested from nuclear weapons in the 1980s and 90s when they declared themselves to be Nuclear-Free Zones (NFZ). Some of these continue to retain their commitment to be free of nuclear weapons investments, including Oakland, Berkeley and Marin County in California, Takoma Park in Maryland, and others across the US.[16]

More recently, the cities of Northampton and Easthampton, Massachusetts have committed to divestment from nuclear weapons, as have Spokane, Washington and Corvallis, Oregon. The City Council of Cambridge, Mass, voted to divest its pension fund from nuclear weapons in 2016 but was blocked by the state.[17]

After a long and arduous effort by campaigners in New York City, the City Council finally voted to divest its $250 billion pension fund from nuclear weapons in 2021.[18] Only about $480 million of this is invested in nuclear weapons companies, but it could have a powerful impact on the companies because of the example it sets for other cities.[19]

Nuclear companies vulnerable to divestment

Which nuclear weapons companies may be most vulnerable to divestment? Of the top 20 nuclear weapons companies, Boeing currently receives the largest share of outside investment. Only 6% of its business is in nuclear weapons. Boeing is also the only nuclear weapons company on Fortune magazine’s list of top 25 “most admired companies.” It values its reputation as a blue-chip company that financial advisors recommend for investment. Being targeted for divestment because of their involvement in producing “controversial” nuclear weapons could hurt Boeing’s status as a blue-chip company that financial advisors recommend for investment.

Airbus has an even tinier stake in nuclear weapons. Its contract with the French government for its part in the production of the M51 nuclear missiles accounts for less than 1% of their total revenue. According to Airbus itself, nuclear weapons programs “are not material to Airbus overall revenues.”[20] Airbus is registered not in France (its customer) but in the Netherlands. This makes Airbus more vulnerable to the TPNW than any of the other nuclear weapons companies, since the Dutch parliament voted to support the Treaty and instructed its government to take part in the negotiations. When, at some point, the Netherlands joins the TPNW, Airbus could find itself in direct violation of Dutch law. Several banks, insurance companies and pension funds in the Netherlands have already divested from the nuclear weapons industry, including from Airbus. More divestment is sure to follow.

Legal basis for divesting from nuclear weapons

What is unique about nuclear weapons divestment is that there is now an international treaty, the TPNW, that not only bans these weapons but bans all “assistance, encouragement and inducement” in support of these weapons. This “assistance clause” uses the identical wording found in other recent treaties that ban landmines and cluster bombs. A number of countries have interpreted that clause in those other treaties to mean a prohibition on financing the prohibited weapons.[21]

Countries who are party to the treaty are legally obligated to take steps to enforce this provision, and that potentially includes making it illegal to finance companies involved in the nuclear weapons industry. Since almost all of these companies have branches, offices, projects, investors, suppliers, etc. in numerous other countries, this could start to affect them directly.

[1] These are that their divestment policy must be public, it must apply to all their products and services, and it must exclude all nuclear weapons companies and all their activities. See Don’t Bank on the Bomb (2023, July 27). Moving Away from Mass Destruction,ICAN/Pax. (p.15) https://www.dontbankonthebomb.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/PAX_Rapport_DBotB_Moving_Away_FINAL_digi_Single_Page.pdf

[2] Compiled from data in Don’t Bank on the Bomb (2023, July 27). Moving Away from Mass Destruction,ICAN/Pax. https://www.dontbankonthebomb.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/PAX_Rapport_DBotB_Moving_Away_FINAL_digi_Single_Page.pdf

[3] Says VP Maura Kenny “We see that divesting from nuclear weapons is good for business, and life.”

See also bank’s position on nuclear weapons from Mante, R. (2021, May 20). Divesting from Warfare. Amalgamated Bank. https://amalgamatedbank.com/blog/divesting-warfare

[4] See statement on nuclear weapons exclusion at Investment Exclusions Guidelines. (n.d.). https://www.wespath.org/retirement-investments/investment-information/investment-philosophy/investment-exclusions/investment-exclusions-guidelines

[5] Friends Fiduciary. (n.d.). How we Invest https://friendsfiduciary.org/how-we-invest/

[6] See list of ethical funds available at https://weaponfreefunds.org

[7] Vatican launches Committee for Investments. (2022, July 21). Aleteia. https://aleteia.org/2022/07/21/more-transparent-ethical-and-centralized-vatican-launches-committee-for-investments/

[8] See Pontifical Academy of Social Science (2023), Mensuram Bonam: Faith-Based Measures for Catholic Investors, (p.34) which can be downloaded in English from: https://www.cbcew.org.uk/bishop-moth-commends-vatican-document-that-seeks-to-help-catholic-investors-make-good-decisions/

[9] Presbyterian Church (USA). (2020, October 14). 2021 General Assembly Divestment/ Proscription List https://www.presbyterianmission.org/wp-content/uploads/APPROVED-2021-GA-Divestment-Proscription-List.pdf

[10] See, for example, the moves taken by Northampton Friends Meeting in Massachusetts to divest and remove all association with nuclear weapons companies: Slater, A. (2018, June 25). Northampton Quakers Are First to Comply with UN Treaty. NuclearBan.US. https://www.nuclearban.us/northampton-quakers-are-first-to-comply-with-un-treaty/ Other examples include the commitment to divest from the Minneapolis Area Synod of the Lutheran Church (2021). https://mpls-synod.org/wp-content/uploads/RC2021-05-FINAL-Memorial-Concerning-Banning-Nuclear-Weapons.pdf

[11] Hampshire College Investment Policy. (2015, November 13). Hampshire College. https://www.hampshire.edu/offices/board-trustees/hampshire-college-bylaws/hampshire-college-investment-policy

[12] Simon, John, Powers, Charles, Gunnemann, Jon (1972), The Ethical Investor: Universities and Corporate Responsibility, Yale University Press.

[13] Email correspondence with members of the Yale Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility.

[14] See written answers to parliamentary questions from the Irish Minister of Finance: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/question/2021-03-04/38/

[15] See Article 8b.2. in Swiss War Materiel Act of 1996: https://fedlex.data.admin.ch/filestore/fedlex.data.admin.ch/eli/cc/1998/794_794_794/20220501/en/pdf-a/fedlex-data-admin-ch-eli-cc-1998-794_794_794-20220501-en-pdf-a.pdf

[16] See list of Nuclear Free Zone ordinances in the US with links to some city codes at: https://www.nuclearban.us/nfz-ordinances-and-city-codes/

[17] Tegmark, M. (2016, April 4). Hawking Says ‘Don’t Bank on the Bomb’ and Cambridge Votes to Divest $ 1Billion From Nuclear Weapons. Future of Life Institute. (n.d.). https://futureoflife.org/nuclear/hawking-says-dont-bank-on-the-bomb-and-cambridge-votes-to-divest-1billion-from-nuclear-weapons/

[18] The New York City Council—File #: Res 0976-2019. (2019, June 26). https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3996240&GUID=4AF9FC30-DFB8-45BC-B03F-2A6B534FC349

[19] In the 1980s, it was not so much the actual amounts of money being divested that worried the companies, but the fear that this was just the tip of an iceberg that would melt over them if they were not able to nip it in the bud. See Dugger, Ronnie (1987), “The Company as Target: Antinuclear Campaigners Across the Country are Interfering with Business as Usual,” in New York Times Magazine, Sept. 20, 1987.(p.30ff) https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/20/magazine/the-company-as-target.html

[20] Quoted by Susi Snyder (2018), Don’t bank on the bomb.

[21] Countries Ban Investment in Cluster Munitions (2009).Arms Control Association. https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2009-12/countries-ban-investment-cluster-munitions

[1] Apfel, D. C. (2015). Exploring Divestment as a Strategy for Change: An Evaluation of the History, Success, and Challenges of Fossil Fuel Divestment. Social Research, 82(4), 913–937. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44282147

[2] See detailed figures in Knight, Richard (1990), “Sanctions, Divestment and US Corporations in South Africa” in Edgar, Robert (ed), Sanctioning Apartheid, Africa World Press. http://richardknight.homestead.com/files/uscorporations.htm

[3] Wander, N., & Malone, R. E. (2006). Fiscal versus social responsibility: how Philip Morris shaped the public funds divestment debate. Tobacco control, 15(3), 231–241. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2596576/

Boycotts

Boycotts can take many forms, the most well-known being the consumer boycott in which people refuse to buy products from a certain company. Cities, states and other large institutions can also boycott companies by refusing to enter into contracts with them. And educational institutions can boycott companies by refusing to accept research grants and other forms of sponsorship from those companies.

History of boycotts

A worldwide boycott of Nestlé products began in 1977, after Nestlé was accused of indirectly killing babies in a number of poor countries where the only water available to mix with their baby formula was unsafe for drinking. After 7 years, Nestle agreed to stop that practice and comply with an agreed international code of practice. Campaigners subsequently argued that Nestlé was still not complying and the boycott continues.[1]

Boycotts were also a key part of the campaign against apartheid in South Africa. These included a sports boycott that kept South Africa teams out of international tournaments and other countries’ teams out of South Africa. There were also cultural boycotts and consumer boycotts of South African fruits, etc. Another form of boycott was known as “disinvestment,” and involved US corporations like IBM, Ford, Mobil and Coca-Cola pulling out of South Africa or selling their holdings there.[2] Banks refused to do business with South African companies and many other business ties were cut.

It’s impossible to know to what extent these tactics affected the final outcome of free elections and Black majority rule in South Africa. But there’s no question that the world contributed to the downfall of apartheid by economically isolating the apartheid regime, and by stigmatizing the whole concept of apartheid.[3]

These kinds of tactics were also applied to the nuclear weapons industry in the 1980s. At that time, some of those companies also made popular consumer products, so consumers could protest their nuclear weapons involvement by refusing to buy things like table salt and lightbulbs.

In March 1986, the nuclear-free zone movement, emboldened by continuing gains, announced a nation-wide consumer boycott of Morton Thiokol Corporation – one of the top 50 nuclear weapons contractors and the largest producer of table salt in the world (“When it rains, it pours”). Twelve months later, Morton claimed the boycott was having no effect on their business and they remained “proud to be part of the defense industry.”[4] Soon after that, they disappeared from the Department of Defense list of nuclear weapons contractors.[5]

Morton Boycott Promotional Pin

The Morton boycott was followed by a boycott of the telecommunications giant AT&T. This seemed to hit at a raw nerve in the company, at a time of intense competition resulting from the de-regulation of long-distance telephone services. The chairman of the board himself went on a public relations offensive to win back public support, claiming that AT&T played “but a small part” in the nuclear industry.[6] In 1992, AT&T cut its ties with the nuclear weapons business by pulling out of the management of Sandia Labs.[7]

Many industries affected by the nuclear-free zone movement made a desperate bid to dissociate themselves from the nuclear arms race. Ford Motor Company filed a lawsuit against Marin County, California in March 1988 over the county’s nuclear-free zone policy. Ford claimed they had nothing to do with nuclear weapons production, but when evidence of Pentagon contracts were presented at a public hearing, Ford withdrew and dropped the suit.[8] IBM and Hewlett Packard were threatening to sue on similar grounds.[9]

General Electric was one of the largest nuclear weapons producers in the US in the 1980s. They also made light bulbs, refrigerators, washing machines and many other household products. A national consumer boycott of GE products led them to pull out of the nuclear weapons business in 1993.[10] To this day, GE maintains a disclaimer on their website to make sure customers know that they have no involvement in the nuclear weapons business.[11]

G.E. Boycott Promotional Pin

There is no direct evidence of the impact these policies may have had on the nuclear industry. Nevertheless, the fact that companies were taking out lawsuits, publicly denying involvement, publishing disclaimers and pulling out of the nuclear weapons business is an indication of how seriously they took these actions against them.

Boycotting fossil fuels

Most of the big so-called “defense contractors” sell their wares to governments. (That’s why it’s such a lucrative industry.) But the major fossil fuel companies sell their products to everybody, which makes boycotting them more complicated.

Gas stations, heating companies, and other fuel vendors

While ExxonMobil, Shell, and Koch Industries jazz up their reputations by making products sold to hospitals, most of the other fossil fuel companies almost exclusively produce coal, oil and gas products, like heating oil and natural gas for homes and gasoline for cars. These are supplied to middlemen like gas stations owners or home heating companies, who then sell these products to consumers.

Many of the state-owned oil and gas companies (Gazprom, Rosneft, PetroChina, Coal India, Lukoil, Petrobas, Statoil, etc.) may be targeted for divestment, but they can’t be boycotted, at least not in the US because they don’t sell gas there. Anyway, they don’t lobby in the US, so they don’t directly impact US policies.

That leaves the following major fossil fuel companies who influence Washington and can be boycotted at gas stations across the US:

Table Major Gas Stations

| Koch Industries | KwikStar, KwikTrip, Tobacco Outlet[1] |

| Phillips66 | Phillips66, Conoco, 76 |

| ExxonMobil | Exxon, Mobil |

| Chevron | Chevron, Texaco |

| Shell | Shell, Stop & Shop, Ranger, Road Ranger, Circle K |

| BP | BP, AMOCO, QuickTrip |

| Marathon | Marathon, Arco, ExpressMart, Wow, Speedway |

| Valero | Shamrock, Beacon, Diamond Shamrock |

Hospitals

ExxonMobil supplies hospitals with syringes, IV bags, face masks, and gloves.[2] Shell also supplies PPE as well as pill bottles and other packaging.[3] Koch Industries, one of the biggest funders of climate disinformation,[4] is also a big funder of medical technologies.[5] If hospitals and other medical facilities were to start boycotting products made by companies whose policies and end products they abhor, that could have enormous impact on those companies.

[1] While Koch Industries cannot be divested from, they can be boycotted.

[2] ExxonMobil. Innovative Healthcare Solutions for Better Patient Care. https://www.exxonmobilchemical.com/en/solutions-by-industry/healthcare-and-medical

[3] Shell. Plastics in personal care products. https://www.shell.us/business-customers/shell-polymers/plastic-personal-care.html

[4] Campaign against Climate Change. (2023, March 27). The funders of climate disinformation. https://www.campaigncc.org/climate_change/sceptics/funders

[5] Reich, D. (2018, February 1). Koch Industries completes second stage of investment in medical device company InSightec [Press release]. https://kochdisruptivetechnologies.com/koch-industries-completes-second-stage-of-investment-in-medical-device-company-insightec/

Boycotting nuclear weapons

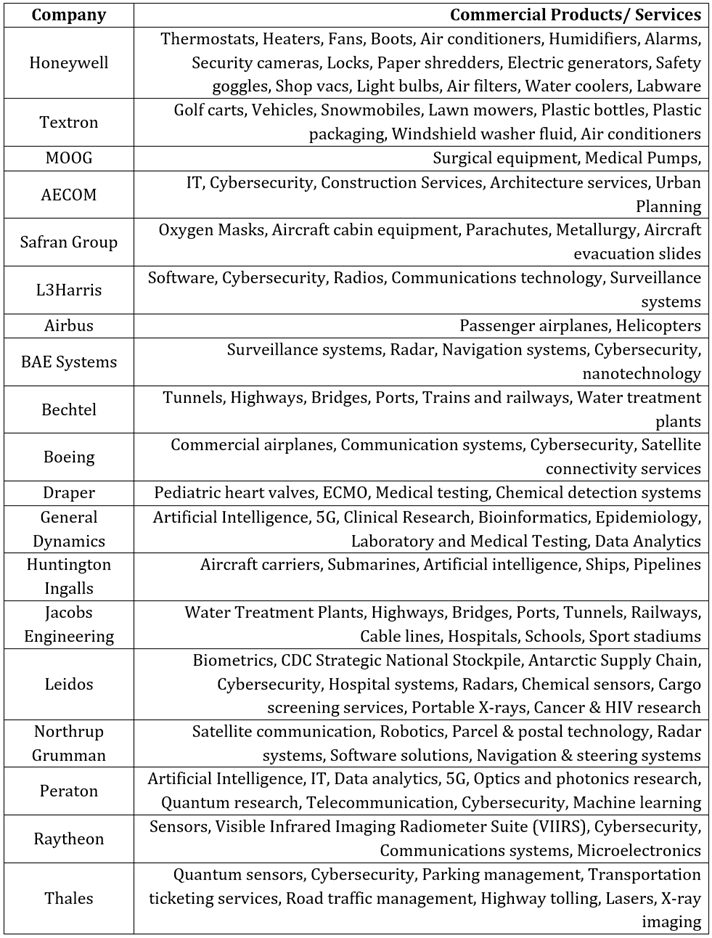

Table: Non-Nuclear Products of Nuclear Weapons Companies

University research boycotts

At least 50 US academic institutions conduct research related to development of nuclear weapons infrastructure, either independently or directly in cooperation with one of the companies involved.[1]

The University of California system goes beyond research: it is directly responsible for managing one of the main nuclear weapons laboratories.[2] Together with Texas A&M and another private company, the University of California manages the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which designs, tests and produces plutonium “pits” that are the core component of a nuclear weapon.[3]

Student and faculty pressure from within the University of California and from other academic institutions could send a very powerful signal to the nuclear weapons establishment and begin a shift in the mentality that takes nuclear weapons for granted.

Hospital equipment

More than half of the top 20 nuclear weapons producers also make medical equipment and/or provide other technical services to hospitals and healthcare providers. Draper Labs, for example, makes pediatric heart valves.[4] Honeywell produces ventilators, CPAP machines, blood pressure devices and other equipment especially for hospitals and other medical facilities. Textron makes air ambulances and other medevac equipment.[5] Jacobs Engineering builds entire hospitals. [6]

That might not be a substantial source of their income, but, as we mentioned above, it’s important for their reputations that they can claim to be helping to improve people’s health and well-being while they are also making weapons that could destroy all life on earth. A campaign by hospitals and healthcare professionals to boycott these companies could therefore have a significant impact.

City and state-level boycotts

Local governments can boycott companies by refusing contracts to buy their bigger products, like highways and water treatment plants. Some municipal efforts to refuse contracts with nuclear weapons companies have run afoul of state laws requiring cities to give contracts to the lowest bidder without exceptions.[7] However, many of those local ordinances are still in place and being implemented. Others have required tweaking to stay within the law.

The City of Oakland, California, for example, passed a Nuclear Free Zone ordinance in 1988 with far-reaching prohibitions, divestment, and denial of contracts with nuclear weapons companies. The federal government took them to court, saying that the City of Oakland had no jurisdiction over the Port of Oakland, a federal facility. The ordinance was struck down by a federal court, but the City of Oakland simply removed all mention of the Port from the ordinance—and passed it again in 1992. It remains one of the strongest NFZ ordinances in the country.[8]

The mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts issued an Executive Policy Order in 2018,[9] committing the city to divest from nuclear weapons and also to refuse to enter into city contracts with nuclear weapons companies. This required going to the state legislature with a “home rule petition”[10] to be allowed to bypass state laws requiring contracts to go to the lowest bidder. The petition was successfully passed by the state legislature and signed into law by the governor, giving Northampton the right to disqualify bidders from city contracts if they are involved in nuclear weapons production, and setting a precedent for 350 other towns and cities in Massachusetts to follow their example.[11]

Consumer products

Today, few nuclear weapons companies make easily boycotted consumer products, and choices have been reduced to a few odd items like snowmobiles and windshield washer fluid.

The exception is Honeywell. In 2019, they sold their thermostat division to a newly created company called Resideo, which continues to sell the Honeywell brand under license,[12] but many other household products remain directly in Honeywell’s hands. One quarter of their income comes from selling these consumer products, and only 0.4% comes from “missiles capable of delivering nuclear payloads and corresponding services.”[13] Thus, an international boycott of Honeywell consumer products could be devastating to the company.

Commercial, institutional, and government products

All of the major nuclear weapons contractors, along with their sub-contractors and suppliers, make other things too – mostly not for sale in the hardware store, but available to cities, states, and large institutions, and thus vulnerable to boycotting by those entities. These include large-scale construction and infrastructure projects, bridges, airports, schools, hospitals, government buildings, cybersecurity, IT, AI, and communications services.

Cities, states, large institutions, and whole countries can refuse to award contracts to nuclear weapon companies. This is the single most powerful thing such entities can do to help enforce the TPNW and eliminate nuclear weapons from the planet.

Some companies are more vulnerable to boycotts than others. Northrop Grumman, for example, provides products and services almost exclusively for military application and obtains 86% of its income from DOD contracts, so boycotting their other products might not make much of a dent. But companies like Boeing and Airbus, as mentioned above, make mostly commercial products, and thus have more boycott potential.

[1] See Schools of Mass Destruction. (n.d.). These are the universities that help to build U.S. nuclear weapons. https://universities.icanw.org/

[2] UC keeps Los Alamos National Laboratory on cutting edge of science and research. (2018, July 9). University of California. https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/uc-keeps-los-alamos-national-laboratory-cutting-edge-science-and-research

[3] NNSA approves start of construction for plutonium pit production subproject at Los Alamos National Laboratory. (2023, February 9). Energy.Gov. https://www.energy.gov/nnsa/articles/nnsa-approves-start-construction-plutonium-pit-production-subproject-los-alamos

[4] Medical Devices. Draper. https://www.draper.com/business-areas/biotechnology-systems/medical-devices.

See also examples from Textron, Jacobs in footnotes.

[5] Textron. (2019, May 21). Textron Aviation displays special mission strength; showcasing air ambulance configured Citation Latitude at EBACE [Press release]. https://investor.textron.com/news/news-releases/press-release-details/2019/Textron-Aviation-displays-special-mission-strength-showcasing-air-ambulance-configured-Citation-Latitude-at-EBACE/default.aspx

[6] Jacobs. Health. https://www.jacobs.com/solutions/markets/health-life-sciences/health

[7] See for instance detailed legal analysis from Patrick J. Borchers and Paul F. Dauer, Taming the New Breed of Nuclear Free Zone Ordinances: Statutory and Constitutional Infirmities in Local Procurement Ordinances Blacklisting the Producers of Nuclear Weapons Components, 40 Hastings L.J. 87 (1988).

Available at: https://repository.uclawsf.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol40/iss1/3

[8] City of Oakland, CA. Ordinance No. 11478 C.M.S (1992, June 30) Declaring the City of Oakland a Nuclear Free Zone. Retrieved from, https://www.nuclearban.us/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/oak042285.pdf

[9] Narkewicz, D. (2018, September 26) Northampton Executive Policy Order: Supporting the Mitigation and Abolition of Nuclear Weapons https://northamptonma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/11503/Executive-Policy-Order—Supporting-the-Mitigation–Abolition-of-Nuclear-Weapons—Sept-26-2019-PDF?bidId=

[10] Dunau, B. (2019, August 20). Northampton City Council takes stand against companies involved with nuclear weapons. Daily Hampshire Gazette. https://www.gazettenet.com/City-Council-passes-home-rule-petition-to-forbid-city-from-doing-business-with-nuclear-weapons-makers-27862171

[11] City of Northampton, MA. Act No. H.4102 (2020, June 25). An Act Regulating City Contracts in the City of Northampton. Retrieved from, https://www.nuclearban.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/H4102.-HOme-Rule-Northampton.pdf

[12] Though it may just be coincidence, this took place after thousands of campaigners across the country wrote to Honeywell to say they would not be buying Honeywell thermostats until they got out of the nuclear weapons business.

[13] This figure clearly does not include many other nuclear weapons-related services provided by Honeywell. See: Honeywell Defense and Space Fact Sheet(2023, May 19). Honeywell. https://investor.honeywell.com/static-files/8a7299ce-af8a-491e-a923-4e3895ac786d

[1] The campaign continues, but without the widespread support it had in the 1970s and 80s. https://www.babymilkaction.org/nestlefree

[2] Feder, B. J. (1991, July 24). BUSINESSES AVOID SOUTH AFRICA TIES. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/07/24/business/businesses-avoid-south-africa-ties.html

[3] Barnes, Catherine (2008), “International isolation and pressures for change in South Africa,” Accord (19) Conciliation Resources: https://www.c-r.org/accord/incentives-sanctions-and-conditionality/international-isolation-and-pressure-change-south

[4] According to New Abolitionist, February 1987, pg 12.

[5] They were also blamed for the space shuttle disaster which took place in the interim. Greenhouse, S. (1986, February 3). THIOKOL: CONTRACTOR AT BIGGEST RISK. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/02/03/business/thiokol-contractor-at-biggest-risk.html

[6] Quoted in Wallis, T (1992), “The Road to Reykjavik: The Impact of European and American Peace Movements on the Decision to Remove Land-Based Missiles from Europe,” a paper for Peace Movements in the Cold War and Beyond, international conference, LSE, London, Jan 2008. p.10.

[7] Mintz, J. (1992, May 6). ATT TO CUT ITS TIES WITH SANDIA LAB. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1992/05/06/att-to-cut-its-ties-with-sandia-lab/c980765e-dda5-45b4-a991-fa7240466b54/

[8] Maclay, K. (1988, February 21). Nuclear-Free Zone Status Brings Legal, Economic Fallout to Cities. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-02-21-mn-44063-story.html

[9] Nuclear Free America, Memorandum, 21 March 1988. NFA Archives. Oregon State University Special Collections.

[10] See General Electric Boycott Announced (1986)Retrieved from Ann Arbor District Library. https://aadl.org/node/244639 and also interview with Kelle Louaillier, (2012, February 28). General Electric Boycott. Don’t Bank on the Bomb. https://www.dontbankonthebomb.com/general-electric-boycott/

[11] See: General Electric (2020). Military Products. https://www.ge.com/sites/default/files/GEA33634_Military_Products_Feb_2020.pdf

Stigmatizing

On top of divestment and boycotts, shaming and stigmatizing the companies that endanger the world can have a cumulative effect on their morale and ultimately their financial status.

For example, the NRA has been hit by boycotts and other forms of stigmatization which they claim now threatens their future viability as an organization.[1] In a lawsuit taken out against New York Governor Andrew Cuomo and others in May 2018, the NRA claimed they were facing “irrecoverable losses and irreparable harm” because Cuomo’s actions had led insurance companies to refuse to cover their events and activities. The NRA also claimed in their court affidavit that it could soon be “unable to exist as a non-profit” because banks were refusing to provide them with routine banking services. Their most recent financial statements for 2022 show revenue down by more than $24 million.[2]

The nuclear weapons industry is very proud to be applying the very latest technologies to “protect” the nation from its enemies. When this is re-framed as an industry that is going against international norms to produce illicit weapons of mass destruction, the status of the industry can change.

The fossil fuel industry is likewise working very hard to make itself seem indispensable. This is already being re-framed as putting profits over people on a grand scale.

The “value” of a company, or its “market capitalization,” is measured by what people are willing to pay to own stocks in that company. That can be vastly more (or less) than the “real” financial value of the company as measured by their profits and overall balance sheet. The difference is known as the value of “intangibles,” such as the good will of customers, brand recognition, corporate social responsibility, and the general standing of the company in the eyes of the public. On average, at least half of the value of a company comes from these intangibles, and if those are negatively affected by divestment, boycotts and other forms of stigmatization, the overall value of the company can be affected.[3]

Global pressures

As we have seen, the TPNW bans not only the development, production and deployment of the weapons themselves, but also any form of assistance with the development, production and deployment of those weapons. This is the only tool available to the non-nuclear-armed states that has the potential to finally force the nuclear-armed states to comply with the treaty.

A Fossil Fuel Treaty will need to similarly prohibit such assistance in relation to fossil fuel extraction and production in order to put similar pressure on the fossil fuel companies.

All the nuclear-armed states, with the notable exception of North Korea, depend to a greater or lesser extent on private corporations to develop, build and maintain their nuclear arsenals. These corporations in turn depend on private investors, suppliers and other customers to stay in business. And almost all of these corporations depend on investors, suppliers and customers in numerous other countries to maintain their bottom line.[4]

This is how those other countries can have an impact: if they make it illegal in their countries to invest in, sell to, or buy from the complicit companies, it will make business as usual very difficult.

The same goes for the fossil fuel industry. The fossil fuel divestment movement is already huge and still growing.[5] But with the added sanction of a treaty prohibiting investments in fossil fuels, that flow of funds away from the fossil fuel industry would become unstoppable. And that is where the real power of the rest of the world comes into play.

There are already countries, like Ireland, that have gone beyond banning any form of assistance with nuclear weapons—they also impose severe penalties for anyone violating that ban.[6] But many of the countries that are already party to the TPNW have not yet passed such legislation.

Apart from getting more countries to sign and ratify the TPNW in the coming years, the most important goal for ICAN campaigners worldwide is to get the existing parties to the TPNW to tighten the noose on the nuclear weapons companies by implementing national legislation banning any form of assistance to these companies, and by enforcing such legislation.

So far, only a few small island nations in the Pacific have committed themselves to the adoption of a Fossil Fuel Treaty.[7] Several more are members or associates of the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, calling for the phasing out of fossil fuels.[8] Once again, it is up to civil society organizations across the world to push their national governments to divest from fossil fuels, along with cities, towns, faith and educational institutions who are doing so.

And as the Fossil Fuel Treaty moves from being an idea to becoming a reality, it will be extremely important for civil society to be pushing the negotiating countries to follow the example of the TPNW and other recent treaties with regard to the “assistance clause.” There is one guarantee that a Fossil Fuel Treaty will have a real impact on the corporations that still hold such powerful sway over national climate policies: the FFT must include language to prohibit any form of assistance, including financial assistance, to the continued extraction, production and consumption of fossil fuels.

While both sets of companies are subjected to these external pressures from other countries through these treaties, campaigners in the US can be providing internal pressure by pushing for boycotts and divestment from those same companies (“fossil and fissile” divestment). This combination creates a much more powerful threat to their bottom lines. Together, in solidarity with countries around the world, we can put significant pressure on these companies to do the right thing and support green technologies in place of nuclear weapons and fossil fuels.

[1] Dickinson, T. NRA Says It’s in Financial Trouble, May Be Unable to Exist. (2018, August 3). https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/nra-financial-trouble-706371/

[2] Leaked 2022 NRA Financial Documents Show the NRA, in the Face of Declining Membership and Revenues and Expanding Legal Spending, Continues with Optimistic Budget Projections. (2023, March 7). NRA Watch. https://nrawatch.org/report/nra-2023-budget-analysis/

[3] See Ross, J. (2020, February 11). Intangible Assets: A Hidden but Crucial Driver of Company Value. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/intangible-assets-driver-company-value/

[4] See the lists of investors from different countries for each of the main nuclear weapons contractors in the 2021 ICAN/PAX report, Snyder, S. (2021). Perilous Profiteering. In ICAN. PAX and ICAN. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ican/pages/2331/attachments/original/1637141262/2021_Perilous_Profiteering_Final.pdf?1637141262

[5] Over 1,500 institutions responsible for over $40 trillion in assets have so far committed to divesting from fossil fuels worldwide. Stand.earth. (2023). Global Fossil Fuel Commitments Database [Dataset]. https://divestmentdatabase.org/

[6] Violators of Ireland’s Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Act of 2019 face an unlimited fine and up to life in prison if convicted. See Office of the Attorney General. (2019, December 11). Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Act 2019. irishstatutebook.ie. https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2019/act/40/enacted/en/print.html

[7] Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Fiji, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Nuie. See: Fossil Non-Proliferation Treaty Initiative. (n.d.). Pacific countries to spearhead global fossil fuel phase-out effort [Press release]. https://fossilfueltreaty.org/fossil-free-pacific

[8] Denmark, Costa Rica, France, Greenland, Portugal, Ireland, Sweden and Tuvalu are Core Members, along with Quebec, Wales and the state of Washington. New Zealand and the state of California are associate members. See Beyond Oil & Gas Alliance. Who We Are. (2023, September 15). https://beyondoilandgasalliance.org/who-we-are/

[1] See for example the arguments put forward by MacAskill, W. (2015, October 20). Does Divestment Work? The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/does-divestment-work

[2] A number of research studies have stressed that the main and most important effect of divestment is stigmatization of the companies concerned and what that does to their reputation and their overall value (market capitalization). Ansar, A., Caldecott, B., & Tilbury, J. (2013). Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign: what does divestment mean for the valuation of fossil fuel assets? In Stranded assets and the fossil fuel divestment campaign. Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

[3] See, for instance, Hasan, S., Kumar, A., & Taffler, R. (2021). Anxiety, Excitement, and Asset Prices. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3902654

[4] See What are stranded assets? (2022, July 27). Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/explainers/what-are-stranded-assets/

[5] See Sharma, R. (2023, October 26). Top 10 Impacts of Social Media on Business. Emeritus https://emeritus.org/in/learn/impact-of-social-media-on-businesses/