Jump to ~ The Warnings ~ Impacts of Continued Warming ~ Limiting to 1.5°C ~ What Makes Climate an Existential Threat

| If you are reading this, you probably don’t need convincing that climate change is real and that it is being caused by humans. But just how serious a problem is it, and how soon do we need to start really worrying about it? Or is it already too late to fix, or too difficult to fix? Are we already doomed to live on a much warmer planet, in which case our job is to adapt as best we can to the new reality? |

This book is about solutions and about how we can get “them” (the powers that be) to implement those solutions. So ultimately this is a hopeful book. But real hope needs to be based on firm foundations, and that means facing the despair of our true situation and confronting it head on. We cannot get to real hope by pretending things are not as bad as they really are, or that “they” know what they are doing. We cannot even assume that “they” have our best interests at heart.

The reality is that we are up against extremely powerful forces that are so single-mindedly focused on short-term financial gain that they will literally destroy the world if we let them carry on with business as usual. The hope is that there are vastly more of “us” than there are of “them,” and that if enough of us decide that we are not going to let this happen, we can stop it.

The warnings

“If we don’t do the right thing now, our children and grandchildren will face serious problems…”

Carl Sagan, testifying before Congress about climate change back in 1985.[1]

Scientists have known about the causes and consequences of climate change for decades. Long before Carl Sagan’s famous 1985 Congressional testimony about the dangers of climate change, there were scientific papers and secret CIA reports warning US Presidents about the continued unrestricted burning of fossil fuels.

In 1965, President Johnson was already warning the nation: “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels…”[2]

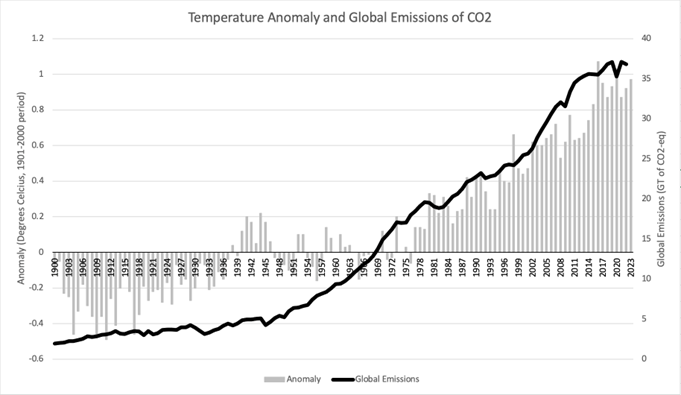

As far back as 1953, warnings from scientists about the continued burning of fossil fuels were making the headlines in leading newspapers around the world.[3] And yet, here we are, 70 years later, with global fossil fuel consumption, the concomitant carbon emissions, and average global temperatures still relentlessly increasing according to virtually every available indicator.[4]

In 1992, the countries of the world finally got together and established the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), aimed at jointly addressing the climate crisis. And yet, every year since then, global carbon emissions have continued to rise, and along with them the global average temperature.

Only in 2020 was there a temporary dip in global carbon emissions, as a result of the slowdown in economic activity at the height of the COVID pandemic.[5] But by 2021, carbon emissions had bounced back up to nearly what they were in 2019, and when official figures are available for 2022, emissions are expected to show that we have reached another all-time high.[6]

We are currently on track for even higher global emissions in 2023, despite all the talk about steps being taken to reduce emissions and all the effort going into achieving the world’s climate goals.[7] And it is now beyond dispute that increasing emissions of greenhouse gases lead directly to increasing average global temperatures.

Since the beginning of the industrial age in the 18th century, global temperatures have already increased by approximately 1.1°C (or 2.0° F).[8] Levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are now higher than they have been for at least one million years.[9]

Figure 2.1 Temperature change and CO2 emissions 1900 to present[10]

Impacts of continued warming

We do not know exactly what will happen if the earth continues to heat up. We do know, however, that if all 24 quadrillion tons of ice that sit on top of Antarctica were to melt, sea levels would rise by more than 200 feet.[11] This would clearly be catastrophic for millions of people who live in the world’s largest cities, the majority of which are situated directly along the coasts of the world’s major oceans and seas.

Most projections of sea level rise refer only to a possible rise of one to three feet by the end of this century. That is nowhere near a rise of 200 feet, but it would already inundate large parts of Florida, Bangladesh and many other parts of the world, and it would cause the disappearance of whole island nations like Tuvalu and Vanuatu, which rise only a few feet above mean sea level.

The problem with climate change is that even small amounts of global warming can lead to all kinds of other impacts, and it is impossible to predict where these might lead. The fact is that glaciers on Antarctica are already melting – and much faster than anyone expected.[12] And loss of ice cover also causes more sunlight to be absorbed by the earth rather than be reflected back into space, causing yet more warming…[13]

Increasing temperatures around the world also lead directly to more extreme drought conditions. So if temperatures continue to rise, this can eventually lead to catastrophic crop failures across many grain-producing areas of the globe.[14]

Droughts occur periodically all over the world and have always been part of the risk that farming communities face. But increasingly frequent, more severe and more extended periods of drought are already affecting growing numbers of people, especially in parts of Africa.[15] As long as water and food are still available from other parts of the world, people in drought-stricken areas need not starve to death.[16] The longer-term danger from global warming is that areas affected by drought could soon overwhelm sources of food and clean water from other areas.

Other effects of uncontrolled climate change include the collapse of ecosystems and the mass extinction of species,[17] mass migration of people as coastal areas flood and extreme temperatures making areas of the world uninhabitable, and extreme weather events causing even more migration and disruption. This is on top of all the physical damage costing trillions of dollars to the global economy.[18]

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C[19]

The Paris Climate Agreement, reached in December 2015, committed every country in the world to doing what they could to prevent global warming from reaching 2°C (or 3.6° F) above pre-industrial levels. But many climate activists at the time felt that a limit of 2°C was already too high to prevent runaway climate change.

In November 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)[20] confirmed their worst fears. The verdict from the world’s leading climate scientists is that allowing global temperatures to increase to 2°C above pre-industrial levels will create instabilities and extremes in global weather patterns which could be catastrophic to human civilization as we know it.[21]

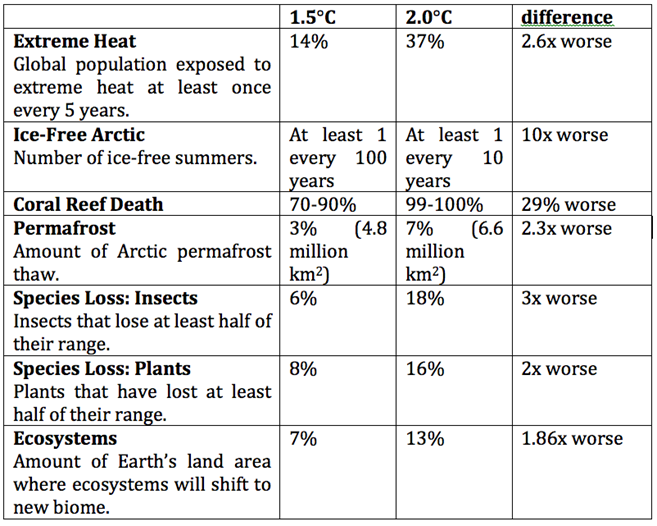

The IPCC’s 2018 report highlights the differences between a world that is 1.5°C warmer versus a world that is 2.0°C warmer. It may seem like a small difference in terms of temperature, but in terms of impact on the human environment, that difference would be significant. For one thing, speaking about a global average temperature can disguise the very large variations that will occur in different parts of the world.

In the tropics, for instance, the difference between a 1.5-degree world and a 2-degree world could be a life and death difference for hundreds of millions of people exposed to more frequent and more extreme heatwaves.[22] That’s because a difference of only 0.5°C in the average global temperature can mean a much larger difference in temperature in places that are already the hottest, and these places are already becoming too hot for normal human activity.[23]

For millions of people living in certain drought-prone regions, the difference between 1.5° and 2 degrees is the difference between having enough food to eat and not. And for millions more living in low-lying coastal regions, the difference is between being able to remain where they are or having to move to higher ground.[24]

All of these increased impacts of a world only 0.5°C warmer than we are already heading towards will fall largely on the world’s poorest communities, especially in small island nations, large parts of Africa, and coastal areas of south and southeast Asia. But no part of the world will remain unaffected by the damage caused by increasingly frequent category 5 hurricanes, wildfires, floods, droughts and other extreme weather events. Millions of climate refugees seeking food and shelter will potentially dwarf the more than 100 million people already forcibly displaced from their homes because of wars, persecution and natural disasters worldwide. And food supplies could be endangered, even for the richest countries on the planet, as harvests fail and fisheries dry up.[25]

Global mean temperatures have already risen by as much as 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels by 2023. The 1.5°C threshold is therefore already getting a bit too close for comfort.

A more recent IPCC report, released in March 2023, has reiterated the dire warning that unless the world makes drastic and immediate cuts to global carbon emissions now, we are heading towards a climate catastrophe of unknown proportions.[26]

Table 2.1 Comparing 1.5 degree world to a 2.0 degree world[27]

Generally speaking, the IPCC is fairly conservative in terms of its analysis of the climate situation, its predictions of where this could lead, and its recommendations for what to do about it. The IPCC represents a consensus view of climate scientists, but its work is also driven by political considerations that determine some of the parameters within which that work is conducted.[28] Other climate scientists and research institutions have been even more dramatic in their predictions of where we are heading if we do not immediately take action to reverse direction.[29]

What makes climate an “existential” threat?

Is it possible, or even likely, that climate change could bring an end to humanity and/or all life on this planet? That may not seem likely in the near term, as most of the impacts described above will impact only certain groups of people at certain times. The rest of us may feel those impacts indirectly, but the totality of human civilization is not in immediate danger.[30]

That is the case for the short term at least. The real impacts of climate change, however, are likely to play out over a much longer time frame than most of us are able to contemplate.

The decisions we make now, and the amount of carbon we continue to pour into the atmosphere, matter not only in the immediate future but over the long term of many decades, possibly even many centuries.[31]

Scenarios of what climate change might mean in the year 2100 already look exceedingly bleak, not just for humans but for a very large number of living species.[32] And almost no one is looking further into the future than that, even though it is known that the impacts of going beyond 1.5°C of warming could affect sea levels and extreme weather events well into the 22nd century.[33]

Climate change may have been at least partially responsible for all the previous mass extinction events in our planet’s history.[34] All living species, including humans, have evolved to survive within certain climatic conditions, and if these conditions change sufficiently, they will not survive. Humans are much more robust and adaptable as a species than most, but we are not immune to the collapse of ecosystems upon which we depend for our survival.

When a large meteor struck the earth 65 million years ago, it was not the meteor itself which led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. It was the sudden change of climate, due to large amounts of soot in the atmosphere caused by fires that followed in the wake of the meteor landing. That layer of soot, which geologists have found embedded in rocks of that same age all over the world, blocked out the sun, creating the exact opposite of the greenhouse effect: a severe cooling of the atmosphere leading to an ice age that killed off 75% of all the species that were alive at that time.[35]

Our survival as a species depends on there being sufficient levels of oxygen in the air, sufficient quantities of drinkable water, and enough nutrition in the food we eat. These, and many other things upon which we depend for survival are only available to us because of very delicately balanced ecosystems involving other living species and their interactions with the natural environment. So even if humans are able to adapt to extreme climate change, many other species will certainly go extinct. And that means the ecosystems which depend on these other species will invariably collapse. Without all the other species of life that sustain all the natural cycles upon which we depend, we ourselves cannot survive.

Climate itself may not be the deciding factor in whether humanity and/or other species survive or face extinction. But climate is a bellwether, like the canary in the coalmine, that indicates the health of the whole biosphere. Therefore climate change, on the scale currently being forecast, can certainly be classified as an existential threat to humans and to millions of other species, even if not to life itself, which has, of course, survived five previous extinction events in the last 3.5 billion years.

[1] See video of proceedings: carlsagandotcom. (2021, August 19). Carl Sagan testifying before Congress in 1985 on climate change. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wp-WiNXH6hI

[2] Johnson, L. (1965, February 8). Special Message to the Congress on Conservation and Restoration of Natural Beauty. [In-Person]. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-conservation-and-restoration-natural-beauty

[3] See New York Times, May 24, 1953, p. B-11: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1953/05/24/282558422.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

K., W. (1953, May 24). How Industry May Change Climate. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1953/05/24/archives/how-industry-may-change-climate.html

[4] Unfortunately, when it comes to carbon emissions, there are a variety of different indicators that are measuring slightly different things. See Chapter 3 for a full discussion of this difficulty.

[5] Most countries submit a report on their carbon emissions to the UN each year, and these are collated with other scientific measurements to produce the most reliable figures for total global emissions of greenhouse gases (CO2-e). This whole process can take up to 5 years, so the most recent official figures from the IPCC as of August, 2023, are from 2019. Other independent research institutions, like the Rhodium Group, compile their own estimates for total emissions when none are yet available from the IPCC, for instance. Rivera, A., et al. (2021, December 23). Preliminary 2020 Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimates. Rhodium Group. https://rhg.com/research/preliminary-2020-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-estimates/. In this report, interim figures are taken from what’s known as the Emissions Gap Report, produced every year by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) as background information for the annual Conference of State Parties (COP) to the UN convention (UNFCCC) that meets to discuss climate commitments. In 2023, COP28 takes place in November in Dubai, and so a new 2023 Gap Report should be out in October 2023.

[6] UNEP. (2022). Emissions Gap Report 2022. In UNEP – UN Environment Programme (pp. 5–6). https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2022

[7] See, for example, Forster, P. M., et al. (2023). Indicators of Global Climate Change 2022: annual update of large-scale indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth System Science Data, 15(6), 2295–2327. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-15-2295-2023

[8] Pachauri, R. K., & Meyer, L. A. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Ipcc.ch (p. 40). IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/syr/

[9] Kahn, B. (2016, September 26). What 2 Million Years of Temps Say About the Future. www.climatecentral.org. https://www.climatecentral.org/news/2-million-years-global-temperature-20733

[10] Graphic by Asher Supernaw, with data from NOAA historical temperature tables and carbon tables in EDGAR: https://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/dataset_ghg80#p1

[11] Bagley, K. (2015, September 11). Climate Change’s Worst-Case Scenario: 200 Feet of Sea Level Rise. Inside Climate News. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/11092015/climate-changes-worst-case-scenario-200-feet-sea-level-rise-antarctica-ice-sheet-melt/

[12] British Antarctic Survey Press Office. (2022, September 5). Seafloor images explain Thwaites Glacier retreat. British Antarctic Survey. https://www.bas.ac.uk/media-post/seafloor-images-explain-thwaites-glacier-retreat/

[13] See report on retreating ice in the Arctic: Osborne, E., Richter-Menge, J., & Jeffries, M. (2018, December 3). Executive Summary. NOAA Arctic. https://arctic.noaa.gov/report-card/report-card-2018/executive-summary-5/

[14] Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D. S., Naylor, R. L., & Ray, D. K. (2018). Future warming increases probability of globally synchronized maize production shocks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(26), 6644–6649. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1718031115

[15] UNHCR. (2023, March). Horn of Africa drought emergency. https://www.unhcr.org/emergencies/horn-africa-drought-emergency

[16] Of course people in drought affected parts of the world do starve to death, not because the food is not available from elsewhere, but because the world still does not prioritize the need to move food to where it is needed over other economic considerations.

[17] Which is also happening as a result of other human activities and not only as a result of climate change. See new UN report on mass extinctions at Ngo, H., et al. (n.d.). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services -unedited advance version. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/5989433/IPBES-Global-Assessment-Summary-for-Policymakers.pdf

[18] Latest IPCC report puts the cost of damage caused by 2°C to the global economy at $69 trillion. See below.

[19] 1.5 degrees Celsius (C) is equal to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (F). Although US-Americans are used to temperatures in F, we use the figures in C throughout this book because this is the universally used language in climate change circles.

[20] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5 oC. IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

[21] There are many terms used to describe a worsening climate. Here we reserve the term “catastrophic” for climate change that has made human civilization as we know it no longer possible. While we are already at a point that could be described as a climate “crisis” and are heading swiftly towards a climate “disaster,” we are not yet at the point of a climate “catastrophe” by this definition. See Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5 oC. IPCC, p. 14. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

[22] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5 oC. IPCC. (p. 177). https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SR15_Chapter_3_LR.pdf

[23] Buis, A. (2022, March 9). Too Hot to Handle: How Climate Change May Make Some Places Too Hot to Live. Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. https://climate.nasa.gov/explore/ask-nasa-climate/3151/too-hot-to-handle-how-climate-change-may-make-some-places-too-hot-to-live/

[24] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2018). Global Warming of 1.5 oC. IPCC (p. 178). https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/2/2022/06/SR15_Chapter_3_LR.pdf

[25] According to the World Meteorological Organization, extreme weather events have already cost the global economy more than $4 trillion over the last 50 years, including almost $1.5 trillion in the last decade.

World Meteorological Organization. (2023, May 19). Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water-related Hazards. Public.wmo.int. https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/atlas-of-mortality

[26] “The cumulative scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human well-being and planetary health (very high confidence). Any further delay in concerted anticipatory global action on adaptation and mitigation will miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all (very high confidence).” Lee, H., et al. (2023). Synthesis Report of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) Longer Report. In IPCC (p. 55). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6syr/pdf/IPCC_AR6_SYR_LongerReport.pdf

[27] Data from Justice and Peace. (n.d.). IPCC Report – The Difference Between 1.5 and 2 Degrees | Justice and Peace Office. Retrieved September 15, 2023, from https://justiceandpeace.org.au/ipcc-report-the-difference-between-1-5-and-2-degrees/

[28] Using wood, or “biomass,” as a fuel, for instance, produces more carbon dioxide per unit of heat than using coal, and yet under present UN accounting rules, biomass emissions are considered carbon-neutral and are thus not included in country reports on carbon emissions. Similarly, present UN accounting rules mean that carbon emissions from overseas military activities are not included in the total figures.

[29] See, for example Purtill, C. (2023, August 18). How climate scientists feel about seeing their dire predictions come true. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2023-08-18/lahaina-yellowknife-hurricane-hilary-climate-scientists-watch-predictions-come-true

[30] See interesting discussion of climate as one among many factors that could lead to human extinction in Pappas, S. (2023, March 21). Will Humans Ever Go Extinct? Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-humans-ever-go-extinct/

[31] Even if we stopped burning fossil fuels today, global warming would continue far into the future due to the delayed warming effects that are built into the carbon cycle and the climate system. That means we must not only achieve the climate goals set out in chapter 6 but also prepare for the rocky ahead with climate adaptation measures.

[32] See discussions on looking beyond 2100, for instance at: Boulton, C. A. (2021). Looking to the (far) future of climate projection. Global Change Biology. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15936

[33] See, for instance: Dunhill, A. et al. (2021, September 26). Our climate projections for 2500 show an Earth that is alien to humans. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/our-climate-projections-for-2500-show-an-earth-that-is-alien-to-humans-167744

[34] Pester, P. (2021, August 30). Could climate change make humans go extinct? Livescience.com. https://www.livescience.com/climate-change-humans-extinct.html

[35] See Redd, N. T. (2020, April 27). After the Dinosaur-Killing impact, soot played a remarkable role in extinction. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/soot-dinosaur-impact-180974708/