<– Back to Problematic Approaches to Climate

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA)[1] is the largest piece of climate legislation passed by the US Congress so far. It’s a sprawling document of 274 pages, over 140 sections, and almost 300 amendments. The IRA includes the spending of “at least” $369 billion for climate mitigation.[2]

Most of this is to be spent over a nine-year period. As much as two-thirds of it is in the form of consumer and corporate tax credits. The credits could end up costing the government more than has been estimated, but they could also end up costing less, since they are dependent on how much consumers and companies choose to take up the offer of spending more on green technologies in anticipation of getting a tax break.[3]

Hoops and Loopholes

The IRA has numerous flaws. For example, tax credits for people buying a new or used EV are riddled with conditions that currently rule out more than half of the EVs on the market from qualifying for the full $7,500 credit.[4] For any lower-income individuals trying to benefit from these tax credits through buying a used EV, the IRA requires that the EV price be listed at $25,000 or lower. Since the average used EV went for $27,147 in June 2023, most used EVs will likewise not qualify for these tax credits, again putting EVs out of reach for many Americans.[5],[6]

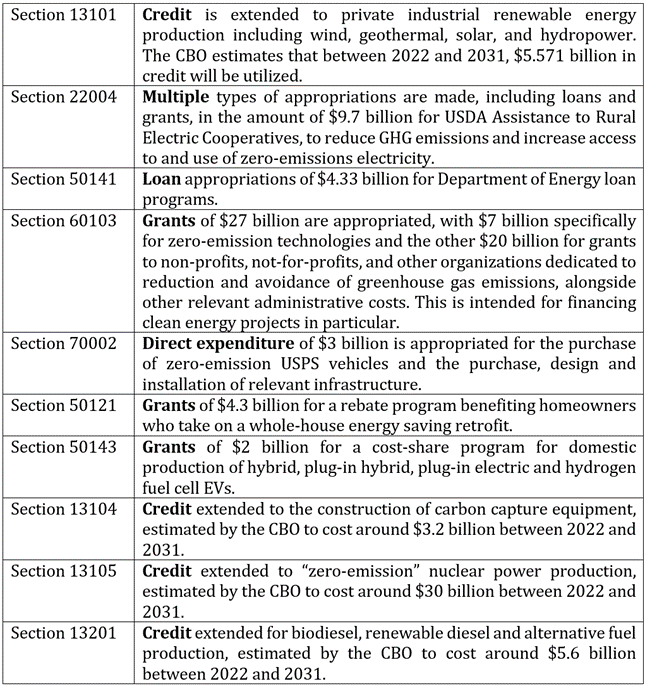

Table 4.3 Examples of IRA Provisions[7]

Tax credits are also available for people putting solar panels on their roofs. But import duties on solar panels originating from China (newly increased for purely political reasons; see China section below) mean that these panels could end up costing more than they did before the IRA, even with the tax credit.[8]

Only about 20% of the funds allocated by the Act are in the form of direct grants, mostly to state and local authorities.[9] State governors, however, hold veto power to reject funding designated to states through the IRA. On June 15, 2023, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis vetoed (purely for political reasons) multiple potential sources of funding for clean energy, including funds designated for Home Energy Rebates through the IRA.[10] South Dakota, Iowa, and Kentucky have also refused funding that was set aside for the largest cities within these states.[11]

The IRA certainly contains important funding and incentives to speed up the transition to EVs, solar and wind-powered electricity, and other climate mitigation measures. But it also relies heavily on nuclear power, biomass, biofuels, carbon capture and other non-solutions discussed above.

It has a built-in commitment to increase oil and gas extraction from federal lands, including in the Alaska reserves and in the Gulf of Mexico. Further, the IRA stops the Department of Interior from leasing for offshore wind unless they have, in the previous year, leased 60 million acres to oil and gas on the outer continental shelf.[12]

Possible impacts

Only one year after it was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden, it is too soon to say how much the IRA will actually make a difference to US carbon emissions, and whether the US is indeed on track to meet its 2030 reduction targets. The Biden Administration claims that the IRA will put the U.S. on a path to reduce emissions to 40% below 2005 levels and, combined with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL)[13] to the 50% reduction needed to keep global warming to 1.5C.[14]

However, a report from 2023 suggests that without the IRA, US emissions would have fallen by 25-31% by 2030, while with the IRA and the BIA, they will fall by 33%-40%. In other words, the IRA is only expected to create an improvement of around an 8-9% in real greenhouse gas reductions by 2030.[15] Another study estimates that the IRA will lead to an additional decrease in emissions ranging between 439 MMT to 660 MMT beyond what would occur without the IRA.[16] This would mean that the IRA would only spur approximately one-fifth of the required decrease in carbon emissions to meet the US’s 2030 target.

And of course, whatever reductions the IRA will cause to carbon emissions will be primarily limited to the US.[17] There has been a great deal of hype around the Biden administration’s “return” to the climate table (President Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement on his first day in office) and how much the IRA will encourage other countries to take their climate commitments more seriously.[18] However, by building into the IRA so much emphasis on buying American and especially on not buying from China, the overall impact of the IRA on global climate goals may turn out to be very different from what was intended.[19]

China and the Geo-politics of the IRA

China currently produces 85% of the world’s solar PV cells, 60% of the world’s windmill blades, 50% of the world’s EVs, and almost 80% of the world’s EV batteries. It controls 59% of the world’s current extraction of lithium and 73% of the world’s cobalt, two of the most critical minerals needed for green technologies at present.[20]

In the short term this means that US efforts to cut imports and supply chains from China are creating shortages and driving up costs of the very things needed to successfully reduce carbon emissions in the US. In the longer term, China’s ability to reduce its own carbon emissions is potentially being curtailed by a trade war which is already hurting the Chinese economy and threatening to derail its ambitious green energy revolution.[21]

Global warming does not stop at national boundaries. It affects all countries equally. And it can only be addressed if all countries cooperate to reduce the combined carbon emissions of all those countries. Almost a third of the world’s population lives in China. Almost a third of the world’s carbon emissions come from China.

The only sensible way to address the climate crisis is to work with China to reduce those emissions. From that perspective, the Inflation Reduction Act is actually a dangerous step in the wrong direction.

Carbon pricing and carbon tax

Carbon pricing, or imposing a carbon tax, involves charging people and industries and governments for the carbon they emit, incentivizing an economic shift toward lower carbon emissions. It gets a lot of attention, but does it work?

A 2020 global study of 43 countries that have instituted carbon pricing of one kind or another showed that, with other affecting variables controlled, carbon emissions in those countries grew 2% more slowly than emissions in countries with no carbon pricing. The study also showed that charging an additional euro per ton of carbon decreased emissions growth rate by 0.3%.[22]

Although emissions rose less slowly in those countries that have tried it, emissions still rose rather than fell during those periods.

The history of carbon pricing so far does not suggest it as a hugely successful way of reducing carbon emissions.

The concept behind carbon pricing is that charging hefty taxes per ton of emissions would be a very quick and effective way to lower carbon emissions.[23] But this would hit a lot of industries very hard, and the costs would be passed on, eventually, to the consumer. The price of nearly all goods, including food, would rise. That would be disproportionately hard on poor families, unless the revenues were carefully redistributed back to communities to offset those negative effects.

Some programs try to address that problem. For example, Canada’s and Chile’s carbon tax revenues are used to lower the tax burden for consumers, and Colombia uses its carbon tax revenues to support rural development and environmental projects.[24] In California, 25% of cap-and-trade funds must be allocated to projects in low-income and polluted communities.[25]

But there is huge public resistance to any scheme that costs people more money, and huge political hurdles to setting carbon taxes high enough to make them effective. The schemes that have lasted the longest are the ones that charge very little for the carbon and therefore have very little effect on the overall reduction of carbon emissions,[26] leaving most countries far from their goals.[27]

As a general principle, while an economy is heavily dependent on fossil fuels, putting a price on carbon merely raises the price of all goods pretty much across the board, and does very little to actually encourage growth of green technologies, since these are equally dependent on fossil fuels in the early stages of any transition.[28]

Carbon pricing is equally clumsy and ineffective as a means of redistributing wealth. In order to redistribute proceeds from the carbon tax collected, a whole additional infrastructure is required, which itself costs money and reduces the amount that can be redistributed.

Market forces

Carbon pricing, tax credits and other financial incentives are designed to encourage industry and consumers to reduce carbon emissions and transition to greener forms of electricity, transportation, and heating without being “forced” to do so. These approaches all rely heavily on market forces rather than on government regulations and legislation that both enables and requires this transition to take place.

The basic problem with a market-based approach is that it is precisely the “market” which has given us the climate crisis in the first place. The market encourages people and businesses to find the cheapest way to get what they want. And what they want is to spend less and make more profit.

There were those in the 1960s and 70s who already saw that the world had a limited supply of oil and gas, and thought that the increasing cost of obtaining it would lead – inevitably – to the search for alternatives, so that by now, we would simply be using solar and wind because it is cheaper than getting oil and gas out of the ground.[29]

That has not happened for the simple reason that as the oil and gas started to run dry and the prices went up, the industry could suddenly afford to dig deeper for it and/or find alternative and novel ways to extract it (two examples: fracking and mining shale oil deposits) that were previously “uneconomic” and not worth exploiting.[30]

Relying on market forces will always result in companies searching for the cheapest solution and the best way to get around the restrictions that get in their way of making a profit. And if all else fails, that means putting their resources into making sure that governments can’t or won’t enforce any of those restrictions.[31]Decades of confusing messages and half-baked solutions to address the climate crisis do not negate the fact that there are solutions to this crisis and it is not too late to implement them. The next two chapters explore these solutions in more detail.

[1] Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. (2022, August 16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text/rh

[2] Senate Democrats. (2022). Summary: The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The Senate Democratic Caucus. https://www.democrats.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/inflation_reduction_act_one_page_summary.pdf

[3] The funding includes as much as $259 billion in the form of tax credits. See Badlam, J., et al. (2022, October 24). What’s in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-inflation-reduction-act-heres-whats-in-it

[4] Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Federal Tax Credits for Electric and Plug-in Hybrid Cars. (2023). fueleconomy.gov. https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/tax2023.shtml

[5] Internal Revenue Service. Used Clean Vehicle Credit. (2023, August 3). https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/used-clean-vehicle-credit

[6] Tucker, S. (2023, July 14). Average Used Car Price Held Steady in June. Kelley Blue Book. https://www.kbb.com/car-news/average-used-car-price-held-steady-in-june/

[7] a. Direct expenditure refers to spending mandated by law within a specific time span – it cannot be spent outside of this time span unless the law is modified.

Grants are typically competitive, meaning that the recipient will have to apply for the grant and be selected. It is possible that funds allocated for grants are not all used, for example if there are not enough applications.

b. Loans are funds given to organizations which must be paid back under a timeline specified by each specific loan agreement.

c. Credit refers to tax credits, where companies and other organizations can, as specified in the relevant text, deduct all or part of their expenses from the amount of tax they owe.

Rebates are partial or full reimbursements after spending or purchasing.

Taxes are funds required to be paid by an individual or organization based on a percentage of profits or added to the cost of particular transactions, goods, and services.

d. Congressional Budget Office. (2022). Estimated Budgetary Effects of H.R. 5376, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (p. 10-11). CBO. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/58366

e. Text – H.R.5376 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (pp. 108-271). (2022, August 16). https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text/rh

[8] Solar modules coming from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam are likely to push prices up due to their origin in China. These four countries represented 73.5% of solar modules imported to the U.S. from January to November 2022. While the duties will not come into effect until June 2024, Leo Azevedo, current Head of Procurement at Key Capture Energy, told NPR that within the U.S. solar industry the concern over retroactive tariffs is stifling new orders of panels. Problematically, the ruling is not limited to companies found to be circumventing these duties and requires all companies within these four countries to pay these high duties until they themselves certify that they are not circumventing the Biden Administration’s orders.[8] These tariffs are assigned with respect to the proportion of production within a company linked to China: Trina Solar, for example, is being made to pay a 254% import tariff while Canadian Solar is subject to 16% import tariff. See Hering, G., & Christian, M. (2022, December 2). US finds solar imports from Southeast Asia skirting tariffs; industry alarmed. S&P Global Market Intelligence; S&P Global. https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/us-finds-solar-imports-from-southeast-asia-skirting-tariffs-industry-alarmed-73369249

[9] Badlam, J., et al. (2022, October 24). What’s in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 | McKinsey. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/the-inflation-reduction-act-heres-whats-in-it

[10] Executive Office of Governor Ron DeSantis. (2023). 2023 Veto List. In Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. Executive Office of Governor Ron DeSantis. https://www.flgov.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Final-Veto-List-2023.pdf

[11] Sioux Falls, South Dakota and Davenport, Iowa have already declined these grants. See Aton, A. (2023, July 19). How Biden steered climate money to red states. E&E News; Politico. https://www.eenews.net/articles/how-biden-steered-climate-money-to-red-states/

[12] Comay, L., Clark, C., & Sherlock, M. (2022, September 29). Offshore Wind Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. Congressional Research Service Reports; Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11980

[13] https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3684

[14] Department of Energy. (2022, August 18). DOE Projects Monumental Emissions Reduction From Inflation Reduction Act. Energy.gov. https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-projects-monumental-emissions-reduction-inflation-reduction-act

[15] Bistline, J., et al.(2023). Emissions and energy impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act. Science, 380(6652), 1324–1327. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg3781

[16] Larsen, J., et al. (2022, August 12). A Turning Point for US Climate Progress: Assessing the Climate and Clean Energy Provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act. Rhodium Group. https://rhg.com/research/climate-clean-energy-inflation-reduction-act/

[17] Larsen, K., et al. (2023, July 6). Global Emerging Climate Technology Diffusion and the Inflation Reduction Act. Rhodium Group. https://rhg.com/research/emerging-climate-technology-ira/

[18] See for instance, Colón, F., Christianson, A., & Childs, C. (2023, August 17). How the Inflation Reduction Act Will Drive Global Climate Action. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/how-the-inflation-reduction-act-will-drive-global-climate-action/

[19] See Yep, E., & Yin, I. (2023, February 28). US climate investment plan to challenge China’s dominance in clean energy (S. Prasad, Ed.). S&P Global. https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/energy-transition/022823-us-climate-investment-plan-to-challenge-chinas-dominance-in-clean-energy

[20]Guix, P. R. (2023, April 11). Key transatlantic implications of the Inflation Reduction Act. Elcano Royal Institute. https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/en/analyses/key-transatlantic-implications-of-the-inflation-reduction-act/. See also: Gül, T. (2023). Energy Technology Perspectives. In IEA. International Energy Agency. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a86b480e-2b03-4e25-bae1-da1395e0b620/EnergyTechnologyPerspectives2023.pdf

[21] See McDonald, J. (2023, August 8). China’s July exports tumble by double digits, adding to pressure to shore up flagging economy. AP News; The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/china-trade-economy-united-states-russia-171915b7daf9ba3f8fbd55724680bbb2

[22] Best, R., Burke, P. J., & Jotzo, F. (2020). Carbon Pricing Efficacy: Cross-Country Evidence. Environmental and Resource Economics, 77(1), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00436-x

[23] Carbon Pricing Dashboard.What is Carbon Pricing?. (n.d.). https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/what-carbon-pricing

[24] Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). (2018, November 14). Pollution pricing: technical briefing. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work/putting-price-on-carbon-pollution/technical-briefing.html

[25] Mountford, H., & McGregor, M. (2018). A Carbon Price Can Benefit the Poor While Reducing Emissions. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/carbon-price-can-benefit-poor-while-reducing-emissions

[26] See Plumer, B., & Popovich, N. (2019, April 2). These countries have prices on carbon. Are they working? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/04/02/climate/pricing-carbon-emissions.html

[27] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). Effective Carbon Rates 2021: Pricing Carbon Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/0e8e24f5-en

[28] See pp. 20-24 in Chapter 3.

[29] See, for example, Meadows, Donella, et al (1972), Limits to Growth, Club of Rome.

[30] Economically viable now thanks in part to taxpayer dollars that continue to subsidize the fossil fuel industry even today.

[31] See Chapter 16.