The Warnings ~ Impacts of Nuclear War ~ Nuclear Winter & Famine ~ Accidents & Close Calls ~ Human Error ~ Calculating Risk ~ Existential Threat

| By now, most people are aware that climate change is a potentially life-threatening emergency. They may be at least dimly aware that an exchange of nuclear weapons would be the end of human civilization as we know it, and possibly of all life on earth. But nuclear weapons pose an existential threat to humanity just as assuredly as climate change. And while it may be decades before the effects of climate change make life impossible for millions or even billions of people, an exchange of nuclear weapons could take place at any moment, and life would become impossible within a matter of minutes. |

The fact that we have not had a nuclear war in over 70 years has lulled many people into thinking that nuclear war cannot happen. Indeed, we have been reassured by those in positions of authority that nuclear weapons keep us safe and will never be used.[1] But the belief that the world can continue to hold onto nuclear weapons indefinitely without ever using them is as dangerous as the belief that we can go on burning fossil fuels indefinitely without causing a climate catastrophe.

The warnings

“Unchecked climate change, global nuclear weapons modernizations, and outsized nuclear weapons arsenals pose extraordinary and undeniable threats to the continued existence of humanity, and world leaders have failed to act with the speed or on the scale required to protect citizens from potential catastrophe. These failures of political leadership endanger every person on Earth.” [2]

This is what the atomic scientists are saying.

As with climate change, the scientists – in this case, nuclear physicists – have known about the dangers of nuclear weapons and have warned the world about those dangers since before the first nuclear weapon was ever tested. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father” of the atomic bomb and subject of the blockbuster film released in July 2023, famously called for nuclear weapons to be placed under international control to prevent them from ever being used again.[3]

Even before the first bomb was tested, a group of nuclear physicists, led by Ernst Szilard, wrote to President Truman urging him to halt development of the bomb before it could be used on human beings.[4] Nuclear physicist Joseph Rotblat resigned from the Manhattan Project once he learned what it was leading to.[5] Rotblat spent the rest of his life raising the alarm about the danger of nuclear weapons.[6]

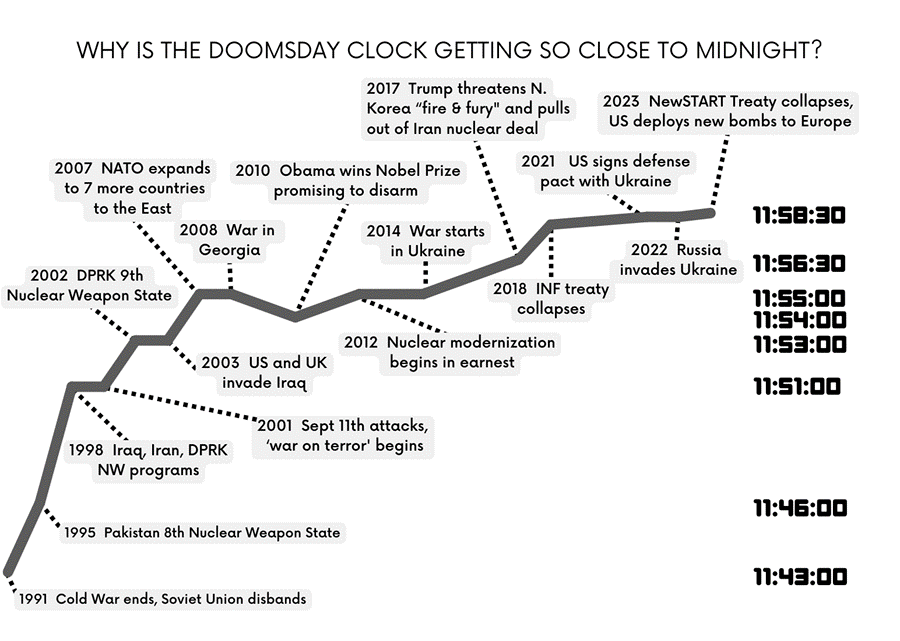

In 1947, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists launched their first “doomsday clock” and set the clock at seven minutes to midnight to alert the world about how close we were to nuclear catastrophe. Since then, the clock has been moved closer and further away from midnight each year, depending on how close the nuclear physicists feel the world is to nuclear holocaust. In recent years, they are also factoring in threats from climate and artificial intelligence.

In 2018, the clock was moved to 2 minutes to midnight, the closest it had ever been since the height of Cold War hysteria in 1953. This was largely because of actions taken by President Trump to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal, threaten North Korea with “fire and fury,” and unilaterally scrap the INF Treaty that had kept medium-range nuclear weapons out of Europe for over 30 years.

In 2021, the clock was again moved closer to midnight under President Biden, and in January 2023, the clock stood at just 90 seconds to midnight, the closest ever amid the strongest possible warning from nuclear scientists that the world is dangerously close to nuclear confrontation.[7]

Impacts of a nuclear war

Nuclear weapons are not just very large conventional weapons. They produce effects that no other type of weapon has ever produced, including temperatures of tens of millions of degrees Celsius that vaporize human beings and shock waves so powerful as to flatten skyscrapers. The impact of even one modern-day nuclear weapon[8] on a single city would cause devastation and suffering on a scale unparalleled in human history. It is the ionizing radiation, however, that potentially causes the most serious and long-lasting effects of a nuclear explosion. This is especially the case if it is a groundburst explosion aimed at a hardened military or government target like a missile silo, nuclear storage facility, or command and control bunker. [9]

Mild radiation poisoning destroys blood cells and damages the genetic material in human cells. More severe forms of radiation poisoning destroy the linings of stomach and intestines, cause internal hemorrhages, loss of electrolyte balance, and heart failure. Death from acute radiation poisoning can take from a few days to several months. Beyond a certain dose of radiation, even the most modern medical treatments are not effective.

Groundburst nuclear explosions produce large amounts of radioactive fallout that can travel hundreds of miles downwind. For example, during one of the largest nuclear tests in the Pacific in 1954, islanders 330 miles from the detonation of a 15 MT hydrogen bomb received accumulated doses of radiation that proved fatal.[10]

The smallest radioactive particles rise up into the upper atmosphere and are dispersed across the entire globe. Even these tiny radioactive particles can be fatal if they enter the food chain and are ingested by humans.

Radioactive isotopes produced by atmospheric nuclear testing in the Pacific in the 1950s were found in the teeth of children as far away as the US.[11] The effects of relatively small doses of radiation are still disputed. However, medical professionals have suggested that as many as 2.4 million people worldwide will have died from leukemia and other cancers as a direct result of radiation from those nuclear tests.[12]

Figure 7.1 History of the Doomsday Clock[13]

This means that if nuclear weapons were ever used again as weapons of war, they would do more than cause cruel and unnecessary suffering to those immediately affected by high doses of radioactivity near to, and downwind of, the explosions. They would also, especially if used as groundburst weapons, cause large amounts of radioactive materials to enter the earth’s upper atmosphere and cause leukemias and other cancers to people hundreds and thousands of miles away.

Nuclear winter and nuclear famine

Nuclear explosions produce fires and intense heat, with dust and soot rising into the upper atmosphere. Most nuclear tests in the 1950s and 60s took place on Pacific islands, barren atolls or in the deserts of western US, central Australia or Siberia.[14] Under these conditions, even groundburst explosions would not be expected to cause major fires, and therefore the soot content was less apparent.

But if a nuclear explosion takes place over dense forest or a densely populated city, fires could be expected to burn out of control for many days over a large area. This happened with nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and with conventional explosives that caused “firestorms” in Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, and other cities during WWII.

During the 1980s there was concern that an all-out nuclear war between the Soviet Union and the West could push so much soot into the atmosphere that it would block sunlight from reaching the earth and lead to a “nuclear winter” – a lowering of global temperatures, causing widespread famine, disease and death of large numbers of people not already killed by the nuclear weapons themselves or from the after-effects of radiation.

At that time, the US and Russia each had nuclear arsenals containing the equivalent of 2,500 million tons of TNT, and climate scientists calculated that an all-out nuclear war would therefore put about 150 million tons of soot into the atmosphere.[15] Using complex computer modeling of the earth’s climate, they estimated that that much soot could lower the earth’s average temperature by as much as 7 degrees C (12 degrees F).[16] This in turn would reduce growing seasons worldwide. Some key grain-producing regions like the Upper Midwest region of the US and the central plains of Ukraine would remain below freezing even in the height of summer and thus be unable to grow anything for up to two years.[17]

Using the same modeling techniques, scientists a few decades later tried to estimate the climatic effects of just 100 Hiroshima-sized bombs, for instance in a regional war between India and Pakistan.[18] Given the population densities in those two countries and the vulnerability of crops to radiation damage, it was concluded that even a “small-scale” nuclear war in that region would have hugely devastating consequences for all the countries across the whole Northern Hemisphere, and could lead to the death of over two billion people.[19]

Just one detonation in a large city today, by accident or on purpose, would kill millions. The immediate casualties would overwhelm the response capacity of the entire global Red Cross/Red Crescent and potentially overfill every burn bed in every hospital on the planet.[20] Women, girls and fetuses would suffer the most from ionizing radiation. Food and water would remain toxic for millions more.

Accidents and Close Calls

Thankfully, in over 70 years of handling nuclear weapons there has never been an accidental detonation of a nuclear weapon by any of the nuclear weapons states. However, the number of times a nuclear weapon could have detonated by accident during that period is alarmingly high.

The most serious accidents involving nuclear weapons took place in the 1950s and ’60s, when US bombers were routinely flying around the world with nuclear weapons on board. In 1961, a B-52 bomber on routine patrol had a leaky fuel tank, caught fire, and broke up in mid-air.[21] Two 4 MT bombs were on board and landed outside Goldsboro, North Carolina. One of the bombs was recovered, and it was discovered that five out of six arming mechanisms had been activated, but the sixth, a cheap low-voltage switch, prevented it from exploding and creating “a very large Bay of North Carolina.” The other bomb plunged into muddy ground at 700 mph and broke up without detonating. More than 50 years later, it’s still there, 180 feet underneath a cordoned-off field, because it would be too dangerous to try to remove it.[22]

In 1966, another B-52 collided in mid-air with a fuel tanker over Palomares, Spain. Four hydrogen bombs were released on that occasion. One fell into the sea and was later recovered, one landed intact with no explosion, and two exploded but only with the outer conventional explosives. Fortunately, though some radioactive materials were released, a full nuclear explosion did not take place.

In 1968, a B-52 crashed in Thule, Greenland, after some foam cushions caught fire in the navigator’s compartment. Four hydrogen bombs were released, but again, the final arming mechanisms prevented them from detonating. Nevertheless, large amounts of radiation were released, requiring a major clean-up operation. Parts of at least one of the bombs were never recovered.[23]

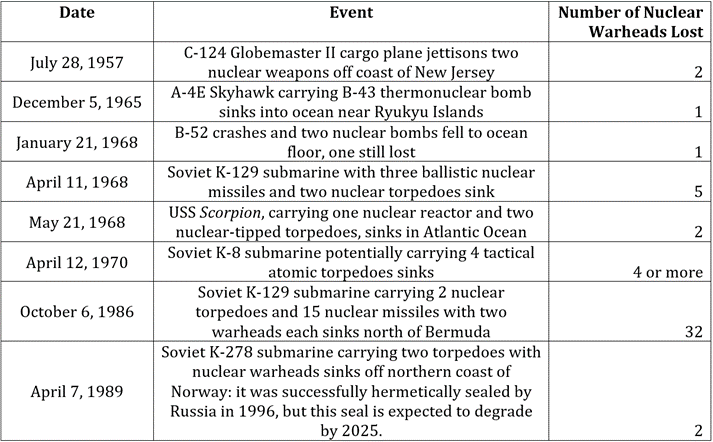

As many as 50 nuclear weapons currently lie at the bottom of the sea.[24] They have rolled off ships, sunk with submarines, and been jettisoned from airplanes. For example, in 1959, a US Navy aircraft dropped a nuclear depth bomb by mistake off Puget Sound, Washington. The bomb sank to the bottom of the sea and was never recovered. In 1968, the nuclear-powered USS Scorpion sank in the mid-Atlantic with nuclear-tipped torpedoes on board. It’s still down there.

In 1986, the Soviet submarine K-219 sank in the mid-Atlantic following an explosion in one of the missile tubes, probably caused by a leaky seal that let salt water mix with the missile fuel, creating an explosive chemical reaction. The K-219 apparently had 15 nuclear missiles on board, each of which contained either two or three 200 kt warheads. All were lost at sea.[25]

In 2000, a Russian nuclear-powered submarine, The Kursk, suffered an explosion on exercise off Norway, probably due to leaking torpedo propellant. The ensuing fire caused seven other (non-nuclear) torpedoes to detonate in a massive explosion detected as far away as Alaska and measuring 4.2 on the Richter scale. Russia claimed at the time that no nuclear weapons were on board, but this has since been disputed.[26] The wreckage of the Kursk was eventually recovered after an enormous salvage operation. None of the men on board survived.

Table 7.1 Nuclear weapons lost at sea[27]

Eric Schlosser, in his 2014 book Command and Control, recounted some chilling moments when some of the largest and most powerful ICBMs ever produced suffered multiple simultaneous malfunctions and came dangerously close to exploding. Some were carrying multiple nuclear warheads, each a thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb.

In the 1980 “Damascus Incident,” a worker accidentally brought the wrong wrench into a missile silo. The 8-pound socket fell off, dropped 80 feet, and pierced the skin of the missile, causing a fuel leak that led to an explosion. One worker was killed, 21 were injured, and the entire complex was destroyed. The 9-megaton warhead was found nearby the next morning in a nearby ditch. Its safety features held, and it did not detonate.[28]

Nuclear weapons are made by human beings and they are managed by human beings. They break down, they have faulty parts, they malfunction, and they get lost. And the people who look after them make mistakes.

Personnel fall asleep on the job, they drink on the job, they take drugs on the job, they forget how to do their tasks and they cheat on tests.[29] In 2003, half of the Air Force units responsible for nuclear weapons in the US failed their safety inspections despite being given a three-day warning that the inspectors were coming.[30]

In 2007, 6 US nuclear weapons went “missing” for several hours because they were loaded onto the wrong plane and sent to the wrong air force base in the wrong state.[31] In 2013, 17 officers with the authority to launch nuclear weapons were stripped of their duties because of a “pattern of weapons safety rule violations, possible code compromises and other failings over an extended period.”[32] In 2016, 14 airmen responsible for guarding America’s ICBM nuclear missiles were disciplined for drug offenses.[33] And in 2023, six officers were fired from Minot Air Force Base over yet another “failed nuclear safety inspection.”[34]

Human error, miscalculation, and miscommunication at the top

There is another element of the human dimension to take into account: the people at the top of the chains of command. Decisionmakers, politicians, generals, policy advisors, etc. can also make fatal mistakes of judgment.

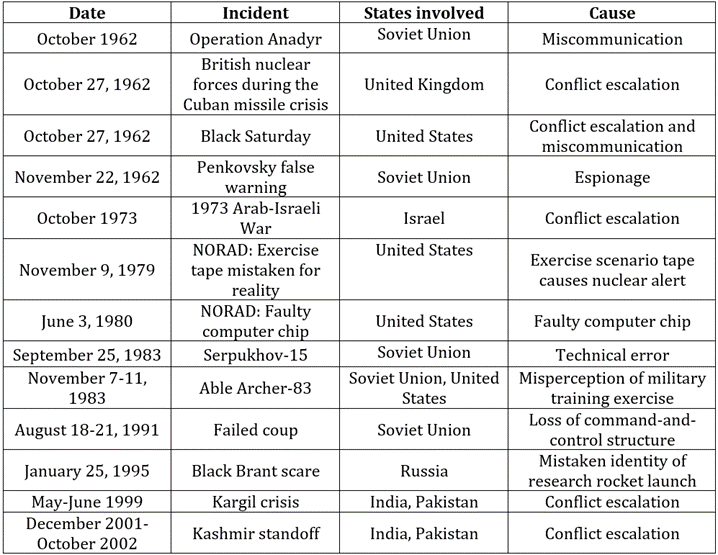

The 2014 Chatham House report, Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy,[35]examined 13 incidents between 1962 and 2002 when the world came perilously close to a nuclear war. All of these cases illustrate the same kind of simple human errors that are compounded by multiple failings into a dangerous scenario that can quickly spiral out of control. In some of these cases, however, we are not talking about the possible accidental detonation of a single nuclear warhead somewhere, but the deliberate, calculated launch of all-out nuclear war involving thousands of nuclear weapons and the certain destruction of modern civilization as we know it.

The most famous of these was the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, which brought the world to the brink of nuclear war in a very public way. But almost no one has heard of the 12 other times that human civilization almost ended in a nuclear conflagration.

For example, in January 1995 a research rocket was launched in Norway. But on Russian radar screens, it looked like an incoming nuclear missile aimed at the Kola Peninsula where Russia’s nuclear submarines are based. The radar operators immediately informed the commander of Russian Radar Forces, who immediately informed President Yeltsin. Yeltsin was handed the nuclear “briefcase” and was on the phone with another general to decide the response when it was calculated that the rocket would land outside Russian airspace and therefore not pose a threat. In this case, the Norwegians had officially informed the Russian government about a research rocket launch, but the message had not been passed on to the appropriate people by the time the launch took place.[36]

Table 7.2 List of “close calls” that almost led to nuclear exchange[37]

In November 1983, a large NATO exercise called “Able Archer” took place in central Europe. It involved a simulated NATO attack on the Soviet Union with nuclear as well as conventional forces. This was during a period of heightened tensions between the Soviets and the west. A Korean Airlines flight with many US-Americans on board had been shot down after flying directly into Soviet territory, the first nuclear cruise missiles had arrived at Greenham Common in England, and US President Reagan had recently made his famous quip about the Soviet Union being an “evil empire.” The Soviets were especially nervous about a possible “first strike” by NATO against the Soviet Union.[38]

NATO planners at the time did not know that, because of the heightened tensions, the Soviets had deployed an intelligence gathering ring to NATO capitals with specific warning signs to look out for and report back immediately if seen. These warning signs would indicate to the Soviets that this was more than just an exercise but actually a cover for a surprise first-strike attack against the Soviet Union.

Two of the signs the Soviets were looking for were the raising of the alert status of NATO bases and the use of new communication channels not previously used. Both of these took place during Able Archer. New “nuclear weapons release procedures” were also in use, raising the level of Soviet concern. Meanwhile, some Soviet forces had been raised to high alert, and the Chief of Soviet General Staff was reputedly already based in a wartime command bunker ready to issue instructions. In the end, a Soviet double-agent in London warned NATO commanders to tone down the exercise before it led to a nuclear war.[39]

Calculating risk

Risk is normally defined in terms of likelihood and consequences. If the likelihood is very, very low (not zero), but the consequences are catastrophic, the overall risk is high because a non-zero probability means that something potentially catastrophic is likely to happen sooner or later. This is the case with nuclear weapons. No matter what precautions are taken and no matter how many failsafe systems are in place to prevent a catastrophe, no government can guarantee that sooner or later a catastrophe will not happen.

There is a parallel with civil nuclear power. In 1975, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission produced a detailed study of the probability of a major accident at one of the 100 US civil nuclear power stations. They calculated the stress factors of different materials used, the likelihood of different parts malfunctioning, the redundancy built into the system to ensure that if one safety component failed another would kick in, and so on.

The report concluded that the probability of a major nuclear generator accident occurring in the United States in any given year, with 100 nuclear power stations operating at once, was one in five billion.[40] Four years later, the worst nuclear accident in US history happened at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant. (Since then, we’ve seen what happened at Chernobyl in Ukraine and Fukushima in Japan.)

The chance of an accidental nuclear weapon detonation in any given year may likewise be one in five billion or some other wildly large number. But that doesn’t mean it can’t happen.

What makes nuclear weapons an existential threat?

When people think of war, they think of a beginning, a middle and an end. They think in terms of escalation and de-escalation, with opportunities to pause, strategize, and choose when and where to execute the war. But…

An actual nuclear war between the US and Russia would be over in a matter of minutes. This is not the kind of war that could be stopped halfway through. There could be no ceasefire or call for negotiations once a nuclear war has started. The nature of modern nuclear weaponry means that as soon as the orders are given to launch on one side, it’s all over for everyone.

The US has a stockpile of approximately 5,400 nuclear weapons. Nearly 1,800 of them are standing by, 24 hours a day, on “hair-trigger” alert, ready to be launched at a moment’s notice with an order from the President, [41] or even through the actions of a rogue military officer with access to the launch mechanisms.[42] A similar number of nuclear weapons are ready to be launched at a moment’s notice from Russia.

These nuclear weapons are not aimed primarily at cities. They may not even be aimed primarily at major air bases or naval ports or large army encampments. The primary targets for US nuclear weapons are Russia’s nuclear weapons and vice versa. Why? Because no conventional weapon is likely to get through several feet of reinforced concrete to the missiles below.[43]

There is enormous military necessity to destroy the other side’s nuclear weapons before they can be fired at you. That is why so many are on hair-trigger alert. These weapons, especially if they are sitting in concrete silos in the wilds of Wyoming or Montana, are targets for a Russian nuclear attack.

“Use them or lose them” is the only strategy available, because if a Russian nuclear attack is on its way, these multi-billion-dollar weapons will simply be destroyed in their silos if they have not been launched by the time the Russian missiles reach them (which takes roughly 30 minutes from launch).

The same applies to nuclear weapons stored at airbases for loading onto strategic nuclear bombers. In the event of a likely attack, these weapons must be loaded onto planes and the planes must take off if they want to avoid being destroyed in a nuclear strike. During the 1950s and 60s, US planes loaded with nuclear weapons were constantly kept in the air for this very reason.

When they’re not literally sitting ducks in port, submarine-launched nuclear weapons are constantly on the move under the waves and are thus considered more difficult to detect and less vulnerable to attack—but that’s changing. Both the US and Russia are spending billions trying to find ways to detect and destroy each other’s nuclear-armed submarines. It’s unlikely, by now, that any Russian sub can leave port without being tracked and monitored by satellites, planes, drones, radio and sonar tracking stations, ships, and other submarines the whole time it is out at sea. The same almost certainly applies to Russian tracking of US submarines.[44]

Even if it manages to hide, the instant a submarine launches a nuclear missile its location will become known and it will be vulnerable to being destroyed. So if they’re going to launch one missile, they’re under tremendous pressure to launch them all.

During the Cold War, making a nuclear first strike wasn’t really a militarily appealing option. Nuclear weapons were still too crude and inaccurate to be able to target and confidently destroy a single concrete silo housing another nuclear weapon. The technology for tracking and destroying submarines was similarly less advanced. So overall, the chances of one side launching a crushing first nuclear strike were relatively low.

The danger with nuclear weapons is not so much that one or two might be launched in anger and that this might eventually escalate into an all-out nuclear war. It’s more likely that one side or the other will think they are under imminent attack and therefore have no choice but to launch their entire arsenal of nuclear weapons before they are destroyed. As during the Cuban Missile Crisis, the more tension or hostility there is between any two nuclear-armed countries, the greater the chance of one or both of them thinking that an imminent attack is possible.

Since the late 1980s and 1990s, the technology of nuclear weapons has sufficiently advanced to make a nuclear first strike more attractive. Strategists may imagine that they could successfully wipe out the opponent’s nuclear force before it could retaliate. Of course, even if that were 100% successful, the whole world would suffer catastrophically from the ensuing radioactive fallout.

The development of strategic missile defenses has also fed the belief that launching a first strike might be acceptable. But despite hundreds of billions of dollars spent, the most sophisticated missile defenses developed so far still cannot be guaranteed to shoot down an incoming nuclear missile before it lands. Meanwhile, the perception that it could succeed might influence a country calculating whether or not to risk launching a nuclear attack.

As long as countries like Russia, China or North Korea keep nuclear weapons on hair-trigger alert, fearing possible attack by the US and therefore ready to launch their nuclear weapons in response, it increases the fear in the US that these countries will launch a nuclear attack on the US and hence the heightened readiness to strike back or to hit those countries before they can launch their weapons.

All of this leads to a spiral of increasing danger that nuclear weapons will be used sooner or later, not in a one-off “tactical” strike by Russia in Ukraine, for instance, but in an all-out nuclear exchange caused by misunderstanding, miscommunication, miscalculation or simple accident, putting an end to human civilization as we know it in a matter of minutes.

[1] For a full discussion of nuclear ‘deterrence’ claims, see chapter 8 here and Chapter 3, in Wallis, T. M. (2017). Disarming the Nuclear Argument: The Truth About Nuclear Weapons(p. 41). Luath Press.

[2] Eden, L., et al. (2015, January 19). Three minutes and counting. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2015/01/three-minutes-and-counting/

[3] This was after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had already killed more than 200,000 people. See Bird, K., & Sherwin, M. J. (2006). American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer. (p. 349). Vintage.

[4] See Gest, H. (n.d.). The July 1945 Szilard Petition on the Atomic Bomb Memoir by a signer in Oak Ridge. (p. 5) Department of Biology at Indiana University. https://biology.indiana.edu/documents/historical-materials/gest_pdfs/hgSzilard.pdf

[5] And Albert Einstein never took part in the Manhattan Project, despite being the one to have alerted President Roosevelt to the possibility of building the Bomb, which he hoped the US would do before Nazi Germany got it.

[6] See Nobel Prize Outreach. Joseph Rotblat – Facts. (2023, September 21). NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1995/rotblat/facts/

[7] See Mecklin, J. (2023, January 24). Current Time – Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/

[8] Today’s nuclear weapons are orders of magnitude larger and more destructive than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

[9] See Section 9.51 in Glasstone, S., & Dolan, P. J. (2022). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons – Glasstone and Dolan | Chapter IX. www.atomicarchive.com. https://www.atomicarchive.com/resources/documents/effects/glasstone-dolan/chapter9.html

[10] Glasstone and Dolan, op cit.

[11] Glasstone, S., & Dolan, P. J. (1977). The Effects of Nuclear Weapons. Third edition. 607. https://doi.org/10.2172/6852629

[12] International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear Weapon estimate that 430,000 people have already died as a result of nuclear tests, and a further two million will eventually die as a result of cancers and other long-term effects, based on data from US National Research Council and UN Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. See IPPNW. (1991). Radioactive Heaven and Earth (p. 164). Zed Books. https://ieer.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/1991/06/RadioactiveHeavenEarth1991.pdf.

[13] Graphic by Asher Supernaw with data from Mecklin (2023) and Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (2022). SIPRI Yearbook 2022. In SIPRI(p. 342). Oxford University Press. https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2022

[14] None of these locations were devoid of people, and indigenous communities bore the brunt of radioactive fallout and its consequences. See below.

[15] Baum, S. (n.d.). Nuclear Winter Archives. Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/publication-term/nuclear-winter/

[16] Robock, A., Oman, L., & Stenchikov, G. L. (2007). Nuclear winter revisited with a modern climate model and current nuclear arsenals: Still catastrophic consequences. J. Geophys. Res, 112(D13), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JD008235

[17] See Webber, P. (2008). Could one Trident submarine cause “nuclear winter”?. SGR Newsletter. https://www.sgr.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-04/NL35_NuclearWinterTrident.pdf

[18] Robock, A., & Toon, O. B. (2010). Local Nuclear War, Global Suffering. Scientific American, 302(1), 74–81. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26001848

[19] See Helfand, I. (2013). Nuclear Famine: Two Billion People at Risk? International Physicians for the Prevention of War. https://psr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/two-billion-at-risk.pdf

[20] Using Washington, DC as an example, one study estimated that 180,000 burn beds would be needed in the case of 10 Kt nuclear explosion over the city, with only 1,000 burn beds available in the whole metropolitan area. See DiCarlo, A. L., et al. (2011). Radiation Injury After a Nuclear Detonation: Medical Consequences and the Need for Scarce Resources Allocation. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 5(S1), S32–S44. https://doi.org/10.1001/dmp.2011.17

[21] Pilkington, E. (2013, September 20). US nearly detonated atomic bomb over North Carolina – secret document. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/20/usaf-atomic-bomb-north-carolina-1961

[22] According to papers released in 2013 under a FOI request. See Johnson, M. A. (2013, September 21). One cheap switch saved US from nuclear catastrophe in 1961, declassified document reveals. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/one-cheap-switch-saved-us-nuclear-catastrophe-1961-declassified-document-flna4b11221026. See also Schlosser, E. (2013). Command and Control. Penguin Books.

[23] See Jorgensen, T. J. (2018, January 23). 50 years ago, a B-52 crashed in Greenland … with 4 nuclear bombs on board. Air Force Times. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2018/01/23/50-years-ago-a-b-52-crashed-in-greenland-with-4-nuclear-bombs-on-board/

[24] Scott, J. (2006, April 2). Broken Arrow Nuclear Weapon Accidents. Aerospaceweb.org. https://aerospaceweb.org/question/weapons/q0268.shtml

[25] See Sudakov, D. (2012, October 9). K-219: The sub that scared Reagan and Gorbachev. PRAVDA.Ru. https://english.pravda.ru/russia/122396-submarine_reagan_gorbachev/

[26] Foreign staff and agencies. (2001, April 5). Kursk “carried nuclear weapons.” The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/apr/05/kursk.russia

[27] Nuclear weapons at the bottom of the ocean are not at risk of causing a thermonuclear explosion, however as the metals corrode and rust, the risk of radioactive leakage is very high and will inevitably affect radiation levels in fish and on up the food chain. Scott, J. (2006, April 2). Broken Arrow Nuclear Weapon Accidents. Aerospaceweb.org. https://aerospaceweb.org/question/weapons/q0268.shtml

[28] See Schlosser, E. (2013). Command and Control. Penguin Books. Also Lewis, P., Williams, H., Pelopidas, B., & Aghlani, S. (2014). Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy. In Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/field/field_document/20140428TooCloseforComfortNuclearUseLewisWilliamsPelopidasAghlani.pdf

[29] See Associated Press. (2014, January 30). Air Force: 92 implicated in nuke cheating scandal. AP News. https://apnews.com/united-states-government-b942adacae524dcfa7fbc85ed6292433

[30] Schlosser, op cit, p. 472.

[31] Wikipedia contributors. (2020, August 27). 2007 United States Air Force nuclear weapons incident. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2007_United_States_Air_Force_nuclear_weapons_incident

[32] Rushe, D. (2013, May 8). US air force strips 17 officers of power to launch nuclear missiles. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/may/08/us-airforce-nuclear-missiles

[33] Martin, D. (2018, May 24). U.S. troops guarding nuclear missiles took LSD, Air Force records show. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/us-air-force-airment-lsd-cocaine-warren-air-force-base-wyoming-nuclear-missile-sites-records-show/

[34] Copp, T. (2023, March 1). Minot firings due to failed nuclear safety inspection. Air Force Times. https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2023/03/02/minot-firings-due-to-failed-nuclear-safety-inspection/

[35] Patricia Lewis et al, op cit.

[36] Patricia Lewis et al, op cit, pp. 16–17.

[37] Ibid.

[38] This is evident from Reagan’s memoirs and other Western intelligence reports, although no archives have been forthcoming from the Russian side to confirm what Soviet leaders were thinking. See Chatham House, op cit, pp. 13–16.

[39]Lewis, P., Williams, H., Pelopidas, B., & Aghlani, S. (2014). Too Close for Comfort: Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy. In Chatham House (p. vi). https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/field/field_document/20140428TooCloseforComfortNuclearUseLewisWilliamsPelopidasAghlani.pdf

[40] U.S. NRC. (1975). Reactor safety study. An assessment of accident risks in US commercial nuclear power (No. WASH1400). http://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:35053391

[41] SIPRI. States invest in nuclear arsenals as geopolitical relations deteriorate—New SIPRI Yearbook out now | SIPRI. (2023, June 12). www.sipri.org. https://www.sipri.org/media/press-release/2023/states-invest-nuclear-arsenals-geopolitical-relations-deteriorate-new-sipri-yearbook-out-now

[42] Personnel in subs, missile silos and planes are not “allowed” to launch nuclear weapons without Presidential authority, but there is no mechanism to technically prevent them from doing so. See Eric Schlosser, op.cit. who claims that “almost everything you saw in Dr. Strangelove was true.”

[43] See proposal for needing non-nuclear “silo-busters”: Geist, E. (2021, October 18). The U.S. doesn’t need more nuclear weapons to counter China’s new missile silos. The RAND Blog. https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/10/the-us-doesnt-need-more-nuclear-weapons-to-counter.html

[44] See Brixey-Williams, S. (2020, August 22). Prospects for game-changers in submarine-detection technology. The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/prospects-for-game-changers-in-submarine-detection-technology/ and NTI. (2021, March 2). Submarine Detection and Monitoring: Open-Source Tools and Technologies. The Nuclear Threat Initiative. https://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/submarine-detection-and-monitoring-open-source-tools-and-technologies/